Note from translator: This essay was first posted by him in Italian on Dec. 2, 2023 at https://www.naibi.net/A/DESMIN.pdf.). My Google-assisted (then corrected) translation first appeared at https://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?p=26381#p26381, after which, in the next post, I gave some of my own reflections on Franco's reflections.

The footnotes are at the bottom of each page, as in Franco's original (the page numbers of his original are in the upper left margin of each).

Where I had doubts about how to translate a word or phrase, I have

indicated them in brackets. They are very few. At one point, Franco says

"voluti arrivare fin qui," which literally would be "wanted to get so

far"; my suggestion was "got so far." Another issue is how to translate

the names of the court cards we call Pages and Knights; the publications

on minchiate speak of Jacks and either "Horses" (in quotation marks) or

Knights. Since the meaning of the term "fante" is one consideration

Franco brings up, as having military connotations (as in "infantry), I have translated it

as "Page," which has that connotation. "Jack" does not; moreover,

speaking of female Jacks is a little awkward: so "Maids" for fantesche. The Italian word for

the Knight card is Cavallo, and the same in chess, and not cavaliere, the usual word for a person with the rank of knight. It makes a difference in Franco's text. Also, the term for the Minchiate suit with gold medallions is called ori; I

had always thought it was denari. Finally, I translated presa (taken)

as "trick-taking power." These are very minor details. Although Franco did review the translation, anything I have missed is on me.

Minchiate, Reflections on Design

Franco Pratesi

1. Introduction

Years ago I wrote

two books essentially dedicated to chess design. [note 1]. My basic approach was that

priority should be given to pieces designed for the game, rather than those

aimed solely at collectors. In reality, chess players will hardly be convinced

by a new model that replaces the traditional Stauntons, even if from a design

point of view it was more valid. I realized that players of any game and sport

tend to be against innovations in professional objects, and I have also

verified a similar situation among card players.

Now I happened to

reflect on the issue in the case of minchiate, because a few weeks ago I had

the opportunity to observe in practice this ancient game of my city. In reality

I have only seen games played with two experienced players and two beginners at

the table. If my practice of the game is poor, this is not strange, because

there have been no experts for more than a century, and only recently

Renzoni and Ricci have learned the game again and are committed to re-spreading

it. [note 2]. However, the experience of observing the difficulties of beginners even

only in "reading" the cards was useful.

Thinking about the

different types of playing cards, we soon come across the difference between

those for players and those for collectors. Sylvia Mann's great teaching, valid

for all cards, should have been a perpetual lesson for collectors: look for the

decks that are played with today in every part of the world and those that were

played with in every era, not those never used to play, even if they show

artistic illustrations as beautiful as you want. [note 3] Yet the many artists who

today undertake to design original decks of cards do so for artistic interest, precisely without taking into account any advantages or

inconveniences for those who use those cards to play. The goal is not for the

newly designed deck to be purchased by many players, but for it to strike the

fancy of enough collectors to purchase it for their own collection. Also when

thinking about a new minchiate deck we soon come across this dilemma.

2. The minchiate deck

The minchiate deck

is unique in the sense that no other tarot deck with 97 cards is known. The

main peculiarity consists of the additional cards compared to a normal tarot

deck of 78 cards, namely the twelve signs of the zodiac, the four elements, the

four virtues that complete the seven overall, minus the Papessa or in

any case one of the Papi, lower tarots [tarocchi].

Even in this case,

decks designed for particular cases, rather than for common play, could be

taken into consideration. Of particular interest were, for example, the

geographical minchiate, also because in those small maps included in each

playing card even remote, newly discovered regions appeared, and therefore still today they are cards of both historical and geographical interest. [note 4]

The

"normal" minchiate, those cards that have passed through the hands of

many players, are usually divided into two main models, defined respectively as

No. 28 and 29 in the Pattern Sheets of the International Playing-Card Society. [note 5]

The first is the older, longer lasting and more widely distributed; the

second is the modern one which, introduced in the eighteenth century, then

became the preference of Florentine card makers and players, especially in the

second half of the nineteenth century, with designs and characters better

corresponding to the fashions of the time, whether in clothing or figure. (In

what follows

__________________

1 F. Pratesi, Scacchi da Venafro al futuro, Tricase (LE) 2017; Pratesi, Observations on Chess Set

Design. Tricase [2018].

2

http://www.germini.altervista.org/

3 S. Mann, Collecting

Playing Cards, London 1966

4 "Atlante tascabile e minchiate del 1780," The Playing-Card, Vol. 47, No. 4 (2019) 252-262.

5

https://ipcs.org/pattern/ps-28.html;

https://ipcs.org/pattern/ps-29.html

2

I will sometimes indicate the second, simplifying, as a

nineteenth-century deck.) As an example, I report two cards of the two models

in the following Figure.

From: http://a.trionfi.eu/WWPCM/decks07/ and Accademia

dei Germini

The structure of

the deck requires some preliminary information, also due to the lack of

uniformly adopted technical terms. In fact, there are different terminologies

for tarot and minchiate, such as to confuse the descriptions if we discuss them

at the same time. Meanwhile, it is always customary to distinguish between

lower and higher cards. Those who use tarot cards for divination solve this

nomenclature problem by introducing two terms that appear appropriate: minor

arcana and major arcana. For me the term major arcana is almost impossible to

accept and that of minor arcana decidedly impossible, because at least in the

"normal" cards I cannot, with all my good will, see anything arcane

at all. The minchiate players called (and therefore the few of today also call)

the lower ones cartiglie - except for the prized Kings - and the higher ones tarots

[tarocchi]. However, it would not be easy to talk about tarot cards as the

superior cards in a tarot deck; there is a lack of suitable terms; I will

thus usually use the term triumphs [trionfi] for the higher cards. I know it's

arbitrary, because in reality triumphs was the name used in the earliest times

for the entire tarot deck, but this way there is less confusion. I will also

not use the term triumph rigidly and will also call a triumph a card when the

context is clear.

So let's take a

closer look at the minchiate deck. As in every tarot deck (except for the

reduced ones, used in other Italian and foreign regions) the "normal"

cards can in turn be divided into the 40 numeral cards, from 1 (Ace) to 10 for

each of the four suits, and the 16 figure [i.e., court - trans.] cards, because instead of the usual

three per suit of ordinary card decks there are 4 here (let's say Page, Knight,

Queen and King), and as we will see, some have additional peculiarities.

The triumphs

(including the Fool, which would usually be considered a card apart) are 22 in

the tarot and become 41 in minchiate. In tarot they can be considered as an

increasing series from 1 to 21, plus the Fool, the twenty-second triumph, to which

the number 0 can be associated and which is

3

independent of the series because it cannot take or be

taken, with rare exceptions. Correspondingly, in minchiate there is the Fool

and a series of triumphs that goes up from 1 to 40 as the order in trick-taking

power [presa].

However, in

minchiate (and not in tarot) there is a further distinction among the

triumphs, which no longer concerns the order in trick-taking but the score

attributed to the given number. First of all, they are divided into counting

cards and cards without value. It is not usual in card games to encounter a high

card that is then worth zero, and this causes some difficulties for beginners.

In my opinion, if you want to design a new deck of minchiate aimed at potential

players, you should somehow indicate directly on each triumph card some

information on the different values of the card itself, and I will return to

this at the end.

3. Reconstruction of a "correct" model

After these

premises, one should be able to reflect on the most suitable way to produce a

new minchiate pack today, in the twenty-first century. However, fundamental

data is still missing. First we must answer the inevitable question: for what

and whom should the new deck be used?

You can consider

the game of minchiate as a game that is now completely dead, neglecting the

attempts to bring it back to life. By doing so, few people are wronged, while

it may capture the interest of scholars of local history, the history of games,

and playing cards in particular.

In short, this new

deck would be a reconstruction that takes into account above all the older

model of minchiate, but with some possible influence also of the

nineteenth-century type, in order to reconstruct a single deck capable of

representing the past of these cards in the most adequate and complete way

possible. It seems like an artificial intelligence job to me; to be completed

based on the countless decks produced in the past by numerous manufacturers,

examined in order to extract the characteristics that distinguish these cards

from others, until the individual details are understood. In short, a sort of

average minchiate pack, as a statistically representative sample; that is, in

such a way as to reduce the many particular decks to one, thus indicating the

entire genus with a single standard example.

However, in this

reconstruction starting from the specimens produced in the past, we encounter

some difficulties. Minchiate figures are traditionally composed of a main

figure and some secondary minor figures of associated objects. For example,

there is no Prudence without a mirror and a serpent that belong to it; but

there are other cases in which the association is not predictable and is due to

reasons that remain more or less unknown to us, such as the porcupine below and

the fox above Libra. It so happens that, for both the main and secondary

figures, over time, changes have been introduced by card makers, even

substantial ones, which in the reconstruction end up forcing us to give greater

weight to the older examples.

Another case in

which - despite recent "progress" in this regard - it would not be

easy to arrive at an average example among those produced in the past, is that

of the sex of certain main figures such as the pages and knights of the suits,

one Pope or two, and even the angel of the Trumpets, who are encountered in the

past drawn either as males or females. Only for Gemini could a Solomonic

solution be found.

There is also a

third difficulty in finding an intermediate model, of a technical nature. What

can the intermediary be between an ancient woodcut and a nineteenth-century

lithograph that now has an almost industrial character? A challenge may come to

mind, so as to technically overcome that dilemma towards current events:

switching to color photographs. I seem to have glimpsed tarot cards on this

technical basis, but perhaps I saw them in a dream: my experience in the matter

is limited. However, it would be enough to gather a group of figures, modify them, dress them appropriately and equip them with the relevant accessories,

including animals and monsters; however, not even Disneyland could propose such

a masquerade, which doesn't seem suitable to me if in fact you want to

reconstruct a standard model of minchiate. 4

Once the task is

finished, one way or another, that same deck can also be used both as a

standard type for divination, provided that it is associated with a booklet

that reveals the arcane meaning of the cards, as well as in the game, provided

that it is also laminated and preferably that it goes into the hands of already

expert players. In short, we would have created an all-round deck. However, it

is possible to more precisely target a new deck of minchiate towards its

specific use; we then encounter not one but two different possibilities of this

kind: precisely, for cartomancy and for game-playing, with different

needs.

4. Minchiate for divination.

The most promising use of minchiate today is

in the sector of divination. After all, minchiate is nothing more than an

extended variant of tarot and today the prevalent use of tarot throughout the

world, is for divination. There are countless tarot decks designed for this

purpose. There are even some packs of minchiate aimed at that market.

Then, once you have

identified a tarot deck that you like among the many, it would just (!) be a matter of introducing some changes to customize it and find designs for the

twenty missing cards as compatible as possible with the existing ones.

Given the fortune of the sector, one might think that the increase in the

number of cards available would be considered an appreciable advantage, even if

one only uses them to predict the future. It is therefore not surprising if a

minchiate pack of this type has already been produced.

Two decks of

minchiate that are certainly new, especially the second, and which cannot be

considered either the average sample indicated above, or the innovative playing

deck that I discuss later, but which could already be used for divination (also

because they are equipped with the necessary booklet or leaflet for the

meanings of the cards) are those of Solleone, designed by Costante Costantini

at a distance of one year apart in the

last century. Even in cases where the figures are very simplified, the

secondary "little figures" mentioned above regularly appear, as can be seen

in the examples in the following Figure.

From: Edizioni

del Solleone - Minchiate fiorentine 1980, and Nuove Minchiate fiorentine 1981

5. Minchiate for the game, among those that exist

We come now to

Florence and the use of minchiate in the game. This presupposes that there is a

certain number, certainly not enormous, of minchiate players intent on reviving

the ancient local game. They will need a

suitable deck.

The first

requirement of such a deck seems in stark contrast to all possible traditional

decks: the two outer surfaces must be laminated! This is the only way to

guarantee sufficient durability and smooth use. The drawing of the figures,

which until now has been fundamental, now becomes secondary, although remaining

important and in need of preliminary discussions to define the possible

contours.

If one intends to

revive the game today, in the twenty-first century, the choice of figures also

has its importance. Is preference given to the first model, let's say from the

eighteenth century, to the second model, let's say from the nineteenth century,

or do we maintain the old game rules but use a newly designed deck? (I would

exclude, at least for now, the possibility of a new deck with which to play a

new game, although someone might also come up with this idea sooner or later.)

The choice of the

first model would mean returning to the origins, when, however, the rules of

the game were already those adopted later. Having to revive a dead game, why

not go back in time as close as possible to its origins? The woodcut matrices

used initially required drawing simple figures, with the bare minimum of lines

in the figure, without flourishes, and the suggestion of these images maintains

its value, without making the past weigh too heavily.

The choice of the

second, nineteenth-century model seems to me to be based less on the

figurative- artistic level, but rather on the historical one. Our elders got so far [voluti arrivare fin qui - wanted to get so far?], and today we take their cards back into our hands to continue

their gaming activity. We use plastic that they didn't know about, but

otherwise we keep the tradition as faithfully as possible. It is then about

5

going into the details, having a ready-made model but with

countless minimal variations in the design of the figures introduced by the

various manufacturers, from which to choose or to modify.

The uncertainty of whether to give preference to model one

or model two, with its relative strengths and weaknesses, can be resolved

with . . . model three, completely innovative.

6. Innovative minchiate for the game

If we intend to

start from scratch in designing a new minchiate pack, we can appreciate the

freedom of no longer being bound by the many constraints to be respected in

reproducing versions of existing models. However, we still encounter

constraints.

The first

constraint, already encountered, is that all 97 cards must have plasticized

surfaces in order to make the cards easier to handle and to greatly extend

their life. Here, however, I must open a parenthesis: Elettra Deganello, who

deals with the matter professionally, pointed out to me that our usual plastic

cards are not as "modern" as I thought. Precisely for the use of

cards in the game, in the USA and other countries have been recently introduced

6

more suitable types of cards, often embossed and with

special finishes, sometimes patented like the one used for Cartamundi's Bee

or SlimLine. [note 6] It will take experts!

Even the dimensions

cannot be just any: you will have to choose average, or better yet below, to

more easily hold the twenty-one cards in your hand that appear at every start

of the game. Possibly, within limits to be evaluated, it will be possible to

increase the height and reduce the width compared to standard formats. Once the

right dimensions of paper have been found, some alternatives must also be

found in the creation of the figures. I try to look at them group by group.

The numeral cards.

The main problem with the 40 numeral cards is the dimensions to adopt for the

suit symbols. After the introduction of modern cards with spades, clubs,

diamonds and hearts we are used to seeing an increasing number of suit symbols,

each with the same design and size. The convenient system of reproducing them

with perforated molds, always using the same module to be repeated several

times, has undoubted advantages. Even for the system - still common in

minchiate but forgotten in many regions - of swords, batons, coins [ori,

literally “golds” - trans.] and cups, the same method of repeating a suit symbol of the

same size can be used. However, this does not appear to be at all convenient

when you have to hold many cards in your hand: in practice this would make it

mandatory to introduce numbers in the margin as indices, visible even with

cards largely overlapping each other.

Thinking of keeping the numeral cards without the index of

the number (also to leave the different numerical series of triumphs unique), it

would be necessary to operate as in Neapolitan cards, i.e. decreasing the

size of the symbols as their number increases, so that you can distinguish

cards of the same suit quite easily even without seeing them in full.

The picture cards. Also in this case minchiate has some significant peculiarities. Meanwhile, the pages of cups and coins are usually females. The matter, even if only

figuratively considered, is not simple. The male pages [fante] are usually

understood as military men, but the female pages [fantesche] are understood more as maids,

which might also suggest the male pages as a kind of butler. Conversely,

thinking of female soldiers nowadays would not be strange, although certainly

foreign to the minchiate tradition. Even more unusual are the figures of the cavalli [meaning both "knights" and "horses']

which at most only have parts of a horse: they would be centaurs for swords and

sticks, while for cups and coins [ori, literally "gold pieces"] figures with human busts above

the lower part of a beast or dragon; in both cases finding a correspondent

among today's people and animals would not be immediate.

Thinking in terms

of trick order, the four court cards of each suit could be denoted by the

numbers 11 to 14, regardless of how you draw the court card. At most, the same

figure might not even be reproduced, leaving the field to just the number,

perhaps with a title block with the name of the figure. However, the peculiar

role of the Kings remains in minchiate (and only in this game, I believe): the

four Kings are in fact the only counting cards among all sixteen courts, and

indeed among all the 56 numeral and court cards. If the counting cards of the

triumphs worth five points were marked in some special way, the Kings of the four

suits could or should also be marked in the same way.

If it were decided

that the numbers added as indexes are useful for marking the card, we encounter

the problem of having to distinguish these numbers from those of the triumphs.

You could think of more possible alternatives to overcome the inconvenience.

The most "traditional" would be to continue using Roman numerals for

the triumphs and thus the distinction with the Arabic numerals of the suits

would be automatic. At most, the triumphs could be marked with Roman numerals

only up to X or XIV, and then with Arabic numerals, no longer being confused

with those of the suits.

The numbers of

triumphs. A first drawback for an updated deck is the Roman numerals

traditionally used on triumphs. Among other things, even those who know them

from school remain confused when faced with numbers like XVIIII and similar

"errors" compared to the classic format. What a disadvantage there

would be in passing

6

https://cartamundi.com/en/playing-card-brands/bee-playing-cards/

7

from Roman numerals to Arabic numerals? None, if you do not

enter the numbers for the low cards [cartiglie]. However, if the low cards have Arabic

numerals as indexes in the margin, the triumphs would not be easy to distinguish

if drawn similarly; therefore, Arabic numerals could be used on the triumphs,

even with very large characters, but without inserting the numbers in the

margin. Or other systems might be found to better distinguish them from those

of the suits. However, it will not be by chance that the triumphs in the tarot cards

most recently used among the players of France and the German-speaking

countries usually have large indexes - and as Arabic numerals! inserted at the top, mostly on both the right

and left.

In minchiate, an

important warning for beginners would be to clearly distinguish the triumphs

with an associated score from the valueless ones. This is an unusual feature

for tarot games and creates some problems. A different color or font or other

identifying mark should be used for counting and non-counting triumphs. As if that

wasn't enough, counting cards don't "count" the same way. There are

three degrees of associated score: 3 points for 2, 3, 4, 5; 5 points (like the

four Kings) for 1, 10, 13, 20, 28, 30-35; 10 points for the Airie: 36, 37, 38, 38 and 40. So the

associated distinguishing marks or colors should necessarily increase.

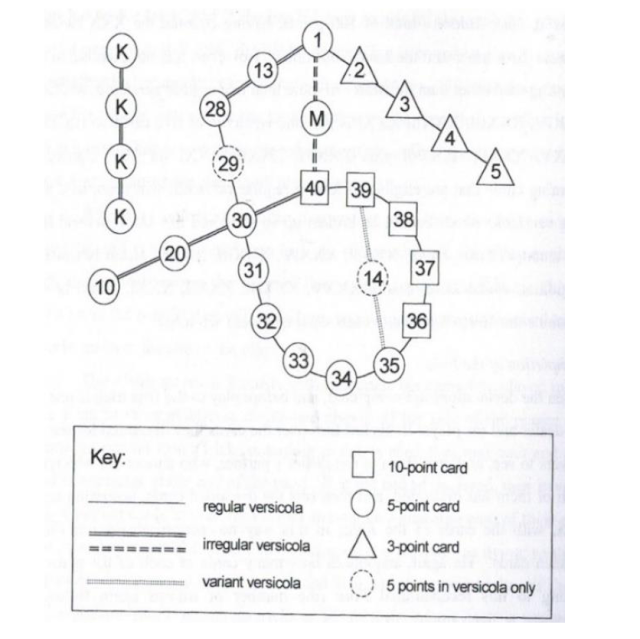

Finally, there is

the problem of indicating, if possible, which triumphs can constitute the

versicole, the typical series of cards that give high scores also because they

are counted at the beginning, during the game and at the end of the game. This

problem has been solved in a definitive way by John McLeod with his diagram

which in one fell swoop indicates both the score value and the formation of

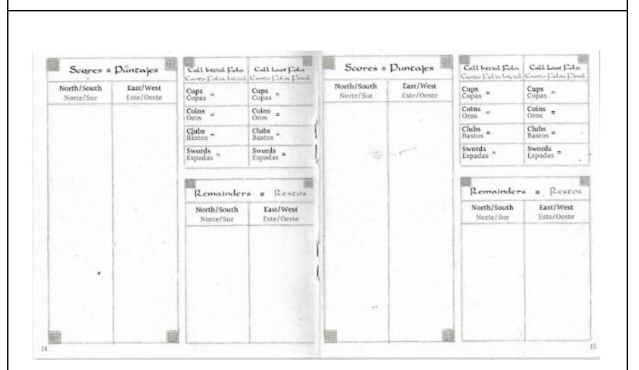

versicules, as shown in the following Figure.

From: M. Dummett, J. McLeod A History of Games Played with

the Tarot Pack. Lewiston 2004, p. 335.

It is not surprising if this diagram appears in every

reference to the rules of the game today.

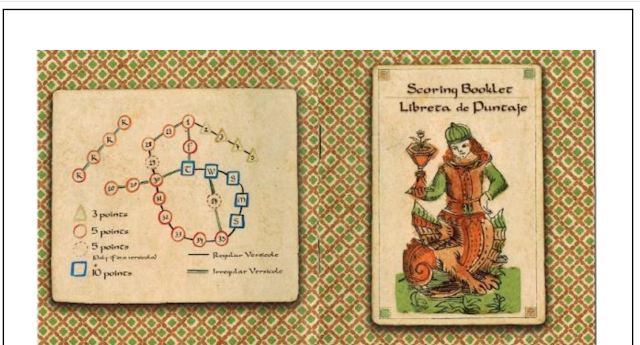

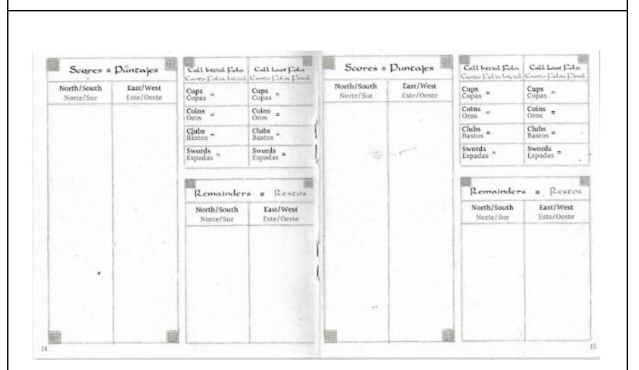

There is even a new deck of minchiate, by Amparo Aguirre,

which has an extra card with this diagram to keep an eye on during the game; [note 7] in another version, the same deck is packaged

in a box together with an instruction booklet and, more unique than rare, with

a booklet of forms for recording the games (see Figure). It doesn't appear that

this deck has solved many of the problems encountered when designing for

players, but it at least takes their needs into account to some extent. One can

hope for a continuation in the "right" direction, considering in

particular the fact that Amparo Aguirre herself is preparing the release of a

new minchiate pack.

___________________________

7

https://tarotminchiate.com/

8

The figures of the

triumphs. For the triumphs, a serious problem is how to represent the corresponding subjects. For an artist this is precisely what becomes the main problem. In the

case of a new deck of minchiate designed for divination, I had advocated as a

working method to first identify, among the countless tarot cards invented for

the purpose, a deck considered preferable and then design cards in the same

style for the additional triumphs present only in minchiate. However, in the case

of a deck for the game, one could perhaps advantageously follow the reverse

procedure: for example, start with a recent artistic representation of the

twelve zodiac signs (there would also be a wide choice 8) and use it for the

new deck of minchiate, then trying to plan the remaining triumphs in the same

style. It is understood, however, that the seven Virtues or the Popes, for

example, will not be easy to draw in a "very recent" form. More possibilities

would be found for the four elements: we could try means of transport: a spacecraft

in a space plasma, a truck on the ground, a ferry on the sea, a plane in the

air; or with other objects in the environment: fire truck, bulldozer,

submarine, hot air balloon; other ideas would not be lacking.

Amparo Aguirre. Booklet for recording the score in a game of

minchiate.

My completely

personal opinion, to overcome the inevitable difficulties of representing in a

current way the mostly chimerical depictions of concepts and personalities from

several centuries ago, is to completely eliminate the problem, removing it

completely, or almost completely, from the artist's task. If someone like me is

not an artist, nor a craftsman in the sector, it becomes possible to replace

each figure of the triumphs with a beautiful title block with the corresponding name

written on it. A word instead of a picture, that is, in as large a font as

possible, easily readable. If desired, with more or less bright colors to leave

some space for the pictorial creativity that has been so severely damaged.

At the limit, again

for someone who does not require traditional artistic contributions to the

design - which will presumably immediately turn away all potentially interested

artists from the idea - one could eliminate even the title block, the

word, and meaning of the card. The extreme limit would be to use its

large central number as the only indicator of the value of the card and, with

the signs or colors or other things that were introduced for the distinction of

the score - everything

_________________________

8

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=signs+of+the+zodiac&form=HDRSC3&first=1

9

needed to play would be present. I fear that this last

solution is the most suitable for absolute beginners or for. . . the 22nd

century; but you never know.

7. Conclusion

The number of new

tarot decks that are offered every year is high, and minchiate is a form of

tarot with the "advantage" of having nineteen more cards.

Unfortunately, in the vast majority of cases the destination of these decks is cartomancy, but it must never be forgotten that they have been used

for centuries to play games commonly considered to be of a high strategic

level. I have discussed various possibilities for designing a new

deck of minchiate, especially in the event that players once again find

themselves willing enough to commit themselves to reviving this ancient

Florentine game, forgotten for a century and a half. I have analyzed several

particular aspects, and this may be useful to anyone who intends to design a

new deck of minchiate; the synthesis, however, indispensable to reach the final

design of an entire new deck, remains open to his or her initiative and

imagination.

Florence, 02.12.2023