Franco's note this time is a transcription of a poem on the evils of gambling. It is a

translation of "Firenze nel Settecento – Ottave sulla bassetta," posted

May 3, 2024, at https://www.naibi.net/A/BASSETTA.pdf.

It concerns bassetta, a banking game, meaning that there is a dealer who takes in losses, pays out winnings, and deals the cards, turning up one card after another. The other players each have one each of all the cards from Ace to King (suits are ignored), on which they place bets. They win or lose depending on what cards the dealer turns up. It is a game of chance in which losers

far outnumber winners, but where the winnings could be spectacular, if

one had deep enough pockets to survive the losses.

In the versions of the game reported later, the banker, called in French the tallière, begins by exposing the bottom card of the deck. This word tallière has no other meaning in French, although there is the word taille, meaning "cut." But how is he a cutter? In this poem, it seems to me, we see the origin of tallière. Exceptionally among accounts of the game, the banker fende,

splits, the deck and lifts the part at the split to expose the bottom

card: this action is known in English as cutting. He is a cutter, Tagliator or Tagliatore, and says "taglio," I cut. The word Tagliatore,

with French spelling, continued even as the action describing him - now

not "splitting" but merely lifting up the deck to expose the bottom

card - ceased to do so and was merely the term for the banker. Such a

person stopped being called even that in casinos (at least American ones

today), but rather the "dealer," representing the "house."

Comments in brackets are mine, in consultation with Franco. Numbers

preceded by "Page" are those of Franco's Italian pdf. Other numbers by

themselves are the stanza numbers. For the reader's convenience, I have

placed Franco's notes on particular stanzas immediately below the

corresponding stanza, instead of at the bottom of the page as in

Franco's original.

Florence in the eighteenth century – Octaves on bassetta

Franco Pratesi

1. Introduction

This study can be considered the continuation of one communicated a

little while ago on other octaves composed on the game of ombre. [note 1] Here

we are in a different environment, because the card game at the basis

of the poetry is now a gambling game, and we are no longer in the

seventeenth century. Although in neither case is the location defined

with certainty, it is clear - also from the documents preserved together

- that we are again in the city of Florence, or at least its territory.

In reality, the historical process of the fashions of card games in

Florence would have led us to predict a reversed presence, in the

seventeenth century, gambling and in the eighteenth century, the

so-called games of commerce or trick-taking. However, we are still

probably in the Medici grand duchy, when the laws intended to combat

gambling were applied with various exceptions, many exemptions, and poor

controls. It will then be the Lorraine grand dukes who will most

effectively combat gambling, which we still see prevalent here.

I intend to copy in full the poetic text of the manuscript preserved in

the Central National Library of Florence [BCNF, Biblioteca Centrale

Nazionale di Firenze], [note 2] inserting

a few notes in comment [in this translation put after each stanza],

before providing some other information on the game and concluding the

presentation.

Florence, BNCF, Fondo Nazionale, II. VII. 51, N. 19

(Reproduction prohibited)

_______________

1. https://www.naibi.net/A/OMBRE.pdf2. BNCF, Fondo Nazionale, II. VII. 51, last insert.

Page 2

2. The octaves

Notes on stanza 1:1 N° 19. On the game of Bassetta. Octaves.

Thirty-one cries, and bambara moans,

primiera has its brow good and wet; minchiate

weeps; [note 3] and Checkers [note 4] languishes, and trembles

[along with] sbaraglino and toccatiglio [note 5]:

In short, all the games cry together,

Because they already had a rigorous exile,

while in the evening everyone hastily runs

to place [note 6] their money on Bassetta.

3. The main card games of all families are recalled, trentuno of banking, bambara and primiera buona of betting, minchiate of trick-taking. Soon pharaoh will take the place of bassetta.

4. Checkers was certainly a very popular game, but there is little information about it before the important manuals of the nineteenth century.

5. Sbaraglino and toccatiglio, properly toccadiglio, were board games of the so-called “racing” variety, later represented especially by backgammon.

6. Because they are placed physically, or via tokens, on top of the card being bet on.

Notes on stanza 2:2

The one who found such a game was for certain

a Distinguished Thief, or rather an Assassin of the Street,

since he taught robbing little by little

without holding his hand to the Arquebus or Sword,

and to rob in any place whatever

alone and defenseless, without a criminal mob,

only fearing a little the Eight, [note 7] or the Quarconia [note 8]

Because the Ban went, but [only] for ceremony. [note 9]

7. The Eight Guards and Bailiffs were a Florentine magistracy in office from 1378 to 1777 with duties of control over various forms of crime.

8. Large building near the Palazzo Vecchio where poor street children were gathered.

9. Clear representation of the poor following of the law. The spread of gambling could not decrease significantly with strict laws that could be easily circumvented.

Notes on stanza 4:3

At the head of a small table, around which

Stand many people, with discomfort and worry,

There is a mountain of money, high and Trivial,

Which urges every soul to possess it,

Here sits the Cutter [Tagliator], who liberally

showing himself to each, intrigues each.

He is called the Cutter, but perhaps

Would be better called the cutpurse [tagliaborse].

4

So starts shuffling the cards

The Cutter when every point is full, [note 10]

And then he fixes his eye everywhere

Inviting [you] to play with a pleasant face

Then he says, I cut [taglio], and with dexterity and art

He splits [fende] the deck, and turns it over in a flash,

but that one who sees his own point in the face

Suddenly becomes afflicted and emaciated. [note 11]

10. When all the bets have been placed on the cards on the table.

11. The first card raised [at the cut, or at the bottom of the deck] gives the dealer an immediate win.

Note on stanza 6:5

To do, he says; and all the others meanwhile

hope that it is under their bet;

but only one person has the boast in order to gain it,

the others exclaim, it's my misfortune,

and someone adds, who is near to the other one

it's not misfortune, no, but madness.

He who thinks he will get rich is a great fool

if only that [number?] below [his bet] wins.

6

At this time the first victor

Folds back [the corner of] the card, [note 12], and then shouts paro [pair];

paro replies the Cutter, and proudly

makes another heart become bitter;

This one sighs, and then haughtily adds,

Go again, but that Go Again costs him dearly,

since if he wins one, he loses many,

and is quickly reduced to broke.

12. This is the signal that you intend to bet on that card again, without withdrawing your winnings.

Page 37

If by luck the card comes in favor of

the one who had the face [the same as the raised card?], he adds, it's done,

Then everyone passes him off as lucky,

Because if he doesn't win it, at least he has a draw

And he keeps luck in his arms.

The one who challenges [boldly] in this way

Then in the long run loses both,

He earns a Horn and wastes an Ox.

8

Full of hope, that one who awaits the pair

Also resolves to make seven for raising, [note 13]

joyful in thought, desires, and claims,

with a small sum, to want to break the bank:

the card comes badly, and the Cutter

takes the money, and that makes him grumble.

He's crazy, then, say the more astute ones,

Note on stanza 8:He who risks his own to gain that of others.

13. Another bet made on the winning card without withdrawing the winnings. [See also stanza 11.]

Notes on stanza 9:9

Such a one, who acts as Satrap, [note 14] and Sage

States that contentment is necessary,

But if this Lord stays to play,

With all his knowledge, he comes out fencing: [note 15]

The Cutter laughs to himself

Because he has nothing other than firm hope,

With such a tasty and useful game,

To make everyone remain without a quattrino [coin = 4 denari, so, “penniless”].

14. Authoritarian figure beyond his merit, from the satraps of the Persian empire.

15. First he invites others to calm down and then he finds himself in a dueling situation.

Notes on stanza 11:10

Therefore he [the Cutter] seeks to make pairs

And give the face [?] to the best better

That he accept the money on the trios

Each one ascribes to singular favor;

But the person who puts it there realizes it, and regrets it

With fiercer disgust, greater pain,

While he almost thinks the bet safe

And until it comes out bad, he's not afraid.

11

To make the paro, the Tagllatore urges,

Seven for raising [levere], and fifteen for putting [porre], [note 16]

And in this way, with careful kindness

Some money won, from [his] hand, [the cutter] knows [how] to take away.

Shouts someone, don't enter this put,

one who doesn’t himself have the virtue of knowing about putting.

Another replies, cancer to Barzini, [note 17]

Who doesn't teach you how to win money.

16. Technical terms for the next two bets on a card, placing a bet instead of withdrawing the winnings. [See Franco’s later discussion.]

17. In the second half of the seventeenth century, for many successive years, Francesco Barzini had calendars with astrological predictions published in Florence; he declared himself a professor of astronomy but there is no trace of him in the Biographical Dictionary of Italians.

Note on stanza 12:12

As this graceful celebration continues, [there is he]

Who blasphemes, who shouts, and who gets angry,

Who bites his hand, and who scratches his head,

Who raises his eyes to Heaven, and who sighs,

Who runs out of money, and who lends it,

Who leaves, who enters, and who turns around [note 18]

But at the end there is not a single one among a hundred,

Who leaves from there happy and contented.

18. Many “who’s” to make us imagine the continuous and frenetic coming and going of people with continuous transfers of money.

Note on stanza 13:13

Even though it contains so many disadvantages,

However, this game is so delicious,

that descend upon it every day, the learned and the Wise,

The miser, the bigot, and the ambitious; [note 19]

Because everyone hopes with great advantage

To win with little, and become wealthy;

but he who persists in gambling knows in vain

that he threw away his money, as into the Arno.

19. Even personages who as a category should logically better resist the temptation to gamble are well represented at the gaming table.

Notes on stanza 14:14

To play it, some people pawn, and sell,

Others take latches, [note 20] with usury,

another who wants to get rich like this

Runs up as much debt as he can get.

Someone, who in another vice, never spends,

In this, wastes without measure

The clergyman plays there, and the Jew,

The Citizen, the Nobleman, and the Plebeian. [note 21]

20. Loans that are unlikely or impossible to repay.

21. Around the gaming table there are categories of people who would have no other possibility of finding themselves together.

Note on stanza 1515

But everyone at the end of the year

cannot boast of moving forward,

but bring from it shame and damage,

And insult the Saints with blasphemy.

Let the Sect [religious fanatics?] come, and Sickness,

Cancer, and Rabies to the Bassettanti [followers of Bassetta]

Whoever doesn't want to lighten his bag and his brain,

This Bassetta, by now, send to the brothel. [note 22]

22. Definitely an unusual ending. The author evidently takes advantage of the feminine gender of the game's name to personify bassetta and send her to work in the brothel, without considering, however, that she could cause loss of money and other damage from there too.

3. Information on the game of Bassetta

I consider it appropriate, also for a better understanding of some passages of the octaves, to provide some elements on the game of bassetta, based mainly on an excellent book on card games from all countries. [note 23] Bassetta is a bank game introduced in Italy as likely

__________

23. D. Parlett, The Oxford Guide to Card Games. Oxford, 1990. [In archive.org, on p. 77.]

Page 4

derived from landsknecht or zecchinetta and then spread throughout Europe, especially appreciated by high-ranking people who could better bear the losses, often high in this game.

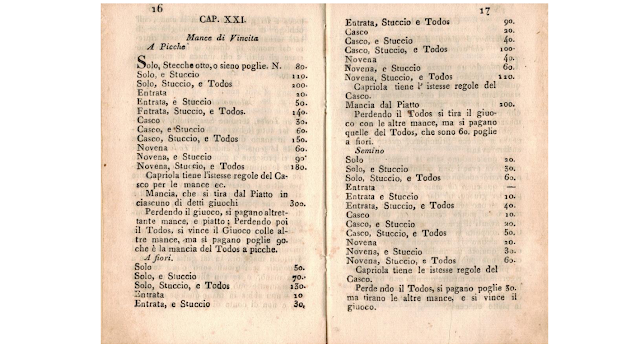

Each of the betting players, in varying numbers but usually four, has a row of thirteen cards in front of them on the table, all those of one suit from the deck of 52; of all the cards only the numerical value from 1 to 13 counts. The dealer has a complete deck of 52 cards in his hand and decides the value of the bet that the players can make (unlike the game of Pharaoh in which the bettors set it) by placing the corresponding number of tokens on one or more of the thirteen cards.

When all bets are in place, the dealer turns over the bottom card of the deck and immediately wins bets made on that card – the same will happen with the last card of the deck [counting from the top]. Then he begins to reveal two cards at a time [dealing from the top of the deck] by placing them in front of the table, one on the right for himself, one on the left for the players. For each pair discovered, the dealer wins all the bets equal to the right card and pays all those equal to the left card. If the two cards are equal they have no effect (while for Pharaoh the dealer would win half the stake).

The player who won, instead of withdrawing the winnings, can bet it again on the same card. This manner of playing is indicated by folding a corner of the card; it is called sept-et-le-va, because in case of a win the player receives seven times the stake. If desired, the same procedure can be repeated three more times, folding other corners of the card and increasing the winnings to 15, then 30 and finally 60 times the initial bet, respectively. The bettor who then loses at any stage pays only the initial stake. Obviously, a winning player believes he has a lucky moment to exploit and so ends up, with rare exceptions, losing even when he had won.

4. Conclusion

The octaves presented can be considered one of many expressions produced against gambling. Card games in other families can find writers and poets who defend them and underline their merits, but for gambling games it is just a vast range of condemnations ranging from the most rigorous to others that are quite reasonable. These octaves as a whole appear rather balanced. The damage to morals, to civil life, to assets, was real, and there is no exaggeration in exhibiting them. But the octaves go further and make it clear that the evil was not in the technique of the game, but in the end was found mainly in the psychology of the player who was unable to give up the chance of winning even when reason would have indicated that it was becoming too meager.

After all, in a game like bassetta, the advantages to the Bank wouldn't be too great. For this game to remain within the limits of an acceptable pastime, two conditions would have been necessary which almost never occurred. The first is, as said, that the player managed to maintain reasonable behavior, and the relative deficiency is well illustrated in the octaves. The second, and this is not highlighted in the poem, is that the dealer maintained correct behavior without resorting to tricks and manipulations capable of greatly increasing the Bank’s advantages.

In short, if it is true that the octaves commented on here express a condemnation of bassetta, it is also true that they could have been even more severe.

Florence, 03.05.2024