This is a translation of Franco's "1498 = Trionfi, libri dei Tornabuoni," originally posted July 28, 2024 at https://naibi.net/A/TORNABUONI.pdf. Comments in square brackets are mine, in consultation with Franco, for explanatory purposes.

1498 – Trionfi, books of the Tornabuoni

Franco Pratesi

1. Introduction

Continuing my research on the Magistracy of Minors collection prior to the Principality[fondo Magistrato dei Pupilli avanti il Principato] in the State Archives of Florence (ASFi), I have examined the manuscript of the Campione series of inventories and accounts, revised N. 181: Quarters Santa Maria Novella and San Giovanni 1495-1501 (part of the 15th Campione).

An inventory of some interest can be found in correspondence with the prestigious Tornabuoni family, certainly one of the oldest in Florence, if we consider that it was born simply with a "strategic" change of surname from the even older one of Tornaquinci (to avoid, as magnates, being ousted from high public office).

After a long presence at the top of the city, in the era in question they found themselves following the Medici themselves closely, including close family ties. In this case, not only the family is known but also the members themselves involved here, starting with the grandfather Giovanni Tornabuoni, who was Lorenzo the Magnificent's uncle and papal treasurer.

The marriage of Lorenzo di Giovanni in 1486 to Giovanna degli Albizzi marked an attempt to bring the two long-adversarial families closer together. This Giovanna was one of the most beautiful young Florentine women, painted several times in portraits and frescoes by Ghirlandaio and Botticelli. The Tornabuoni family was known for its patronage, and among other works, the famous Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella remains in evidence.

Lorenzo was born in Florence in 1465 to Giovanni and Francesca di Luca Pitti, and his closeness to the Medici was fatal to him: together with four other conspirators who intended to re-establish the hegemony of the Medici during the Savonarola republic (destined to end shortly after), he was condemned to death and beheaded in the Bargello Palace on 21 August 1497.

The specific case of the inventory in question concerns the inheritance left by Lorenzo di Giovanni to his ten-year-old sons Giovanni, born to his first wife Giovanna degli Albizzi (who died in childbirth at the age of twenty, at the end of her second pregnancy), and five-year-old Leonardo, three-year-old Francesca and one-year-old Giovanna, children of his second wife Ginevra Gianfigliazzi.

2. Saint Stefano in Pane

The inventories begin on c. 141r with that of 5 January 1498 relating to

one of the villas that the family owned in the Florentine countryside,

in this case, a villa purchased a few decades before in the parish of

Santo Stefano in Pane, and in particular in "Chiasso a Macieregli."

Chiasso Macerelli is a road that goes up from Rifredi to Careggi and in

the twentieth century took the name of Via Taddeo Alderotti.

The Tornabuoni, in addition to their possessions in the area, long had the patronage of the pieve

[main church of a group of parishes, ten or so constituting a diocese]

of Santo Stefano in Pane, and three priests of the family were pieve

priests in the 16th and 17th centuries (elsewhere, somewhat curiously,

as many as four members of the family were bishops of Spoleto during the

sixteenth century). This pieve has always had a particular importance in the area, which continued as it transformed from a country pieve into

a suburban parish in Rifredi, until recently an important working-class

neighborhood with many factories, starting with the Officine Galileo

precisely in Chiasso Macerelli.

To get an idea of this long history, I think the brief description by

Alberto Andreoni on the website of the same parish is sufficient. [note 1]

Before industrialization, the area was especially famous for its

country villas. The panorama of the time is difficult to imagine today,

but the nearby and much more famous Villa di Careggi was similarly at

the center of agricultural estates belonging to the Medici family for

centuries and only recently habitually welcomed writers and

philosophers. In connection with the

_____________________

1. https://www.pieverifredi.it/storia_arte.php

2

Villa Medici in Careggi, there were other villas of rich Florentines

who, like the Tornabuoni, also gravitated culturally around the artistic

and literary environment of the Medici.

Some information on the history of the villa in question, then Villa Lemmi, can also be found on Wikipedia, [note 2] and detailed information is collected in several books; note 3 to see some of the frescoes from Tornabuoni times involved here - found in the 19th century - you have to go to the Louvre.

Villa Tornabuoni Lemmi from Via Incontri (2024)

The inventory of household goods in the villa (purchased in 1469) was

compiled on 4 January 1498; I have reproduced the page in question and

transcribed the elements of interest.

_______________

2. https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Lemmi

3. For example: Villa Tornabuoni-Lemmi di Careggi. Rome 1988

3

ASFi, Magistracy of Minors prior to the Principality, 181, f. 141v (Reproduction prohibited)

In the bed-chamber of the section above said room

One piata [pietà] and one small tabernacle [Typically the container for consecrated hosts on the (church) altar, but could also be a setting for religious images at home]

1 wooden bed frame with walnut cornices and inlay, 4 arm-lengths with supports and cane

1 raw mattress [two sheets sewn together, with stuffing] in two pieces

1 side mattress with old wool

1 striped quilt [choltricie] vergata [?], good, of feathers

2 primacci [large pillows or small quilts] of said bed, weight s. 4

1 pair of used 4-piece sheets

1 thick quilt [coltrone] with cottonwool, good

1 white quilt [choltra] with more work, good

2 good bed pillows

1 set of curtains with hangings around [the bed] as a pavilion

1 covered small bed antique-style of walnut of about 5 arm-lengths with chappellinaio [“hatrack” on wall, thus suitable for various items of clothing]

1 side [?] mattress with green wool cloth [weaving?]

2 pillows, of tapestry and leather

1 pair of pillows for small bed

1 used Parisian-style blanket for small bed, used

4

At f. 144r, after the household goods, the land and house possessions in the area are listed and the second inventory relating to the other country property begins.1 large bed towel

2 chests with 4 fasteners around said bed and in the 1st

1 chalice with enameled silver cup

1 missal in form and 1 piece of press [iron or other pressing device]

1 silver and bone pacie [“peace” tablet kissed during the mass]

1 brocaded altar front with 2 cloths

1 chasuble [liturgical vestment], brocaded

1 embroidered red velvet surplice

1 stole of blue velvet, amice [liturgical garment worn at the neck], and brocaded manipola [or manipolo, strap around the wrist, descending one or two hand-lengths]

1 surplice, used, and 1 amice, used

1 small bell and 2 brass chandeliers

1 book of triumphs of Petrarch

3. San Michele in Castello

Following is the inventory of the villa of the Brache located in the parish of Santo Michele in Castello, a place known as le brache, made on 6 January 1497 [1498 in the current system] by the hands of Bernardo Ughuccioni first and Francescho a Careggi.

If the Careggi area could be considered a

countryside suitable for holidays, that of Castello, further away from

the walls of Florence in the same direction, was perhaps even more so,

and numerous villas built in the area over the centuries on the low

slopes in the foothills of Monte Morello remain as evidence, among which

the famous Medici Villas of Castello and Petraia excel.

As usual, the inventory of household goods refers only to the villa, where the Tornabuoni family holidayed.

5

After the inventory of household goods, f. 146r briefly lists the farms, workers' houses, and cultivated land that the family-owned locally.In Giovanni's room

1 Our lady, painted in gesso

1 Saint Jerome painting

1. Simple bed frame attached to the small bed and chest and chappellinaio [“hatrack” on wall, also suitable to hang other clothing items]

1 raw mattress [?] of 2 pieces with sticks

1 rough fabric mattress with chapecchio [extra thickness at head end?]

2 rough fabric mattresses and 1 with blue fabric with wool

1 mattress of dense cotton or wool fabric full of cotton wool

1 primaccio [large pillow or small quilt] with Lombard filling

3 cotton heavy quilts [choltroni] used on said bed

1 rough fabric mattress with wool

1 Parisian-style quilt [choltre], used on said bed

1cottonwool quilt, used, for small bed

1 pillow of tapestry and leather used

1 platform pierced for invalids

1 chest with 2 fasteners, in antique style

1 simple panel of 3 arm-lengths with trestles

1 dining table at 4 feet by 2 arm-lengths and 1 window covering

1 used walnut table

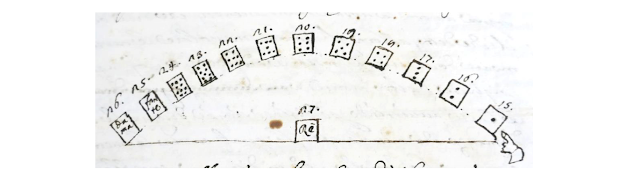

2 books covered in red in form of Guido's [probably referring to Livy's] decades and petrarcha's trionfi

1 pair of andirons of l. 32

1 dustpan 1 pair of tongs and 1 fork

4. The big house

In a rather unusual order, starting from c. 146v, after the inventories of the household goods in the two Tornabuoni country houses, we find the last inventory of this kind, relating to the stately home of the city, the Palazzo Tornabuoni, which still exists near the Palazzo Strozzi, despite renovations repeated over the centuries and with massive reconstructions on the occasion of Florence as capital [of Italy].

Two other houses are also listed, one adjacent, the other also nearby, in Via dei Ferravecchi. I have not seen the date of this inventory, but it cannot be far from the previous ones.A large house with its vaults and courtyard rooms and bedchambers and other homes and apartments located in the parish of Santo Branchazio of Florence and in via de beglisporti.

The inventory occupies eight pages written in two columns and therefore highlights the abundance of objects, as could be expected from the family's well-known wealth. Somewhat surprisingly, we find very few books listed. Of gaming objects we only find a chessboard; that there are no playing cards or triumphs present corresponds to the general situation, such that they are only recorded in extremely rare cases. Instead, some musical instruments appear.

This inventory ends on f. 150r.In the ground floor room in the entrance hall: 1 viola with bow, 2 zufoli [early flutes or recorders?] to play, and 1 chessboard. a bone horn with works. In the chamber of the golden ceiling: 1 large harp for playing.

5. Comments and conclusion

The reason why I have reported this information does not directly concern playing cards or triumphs, but "only" the books of Francesco Petrarch's Trionfi. We are now at the end of the fifteenth century, and finding these books in the homes of ancient Florentine families cannot be a surprise. But there are some open questions about it.

6

An initial question is whether there could have been printed books or manuscripts. If it had been a list of new or very recently produced objects, the choice would plausibly go towards the press, but no one can certify that these books had not been preserved as they were in the family for decades. Incidentally, I don't know of a printed book that contains both the Deche and the Trionfi, but I don't have enough experience in this regard. Personally, however, I am inclined, at least in this case, towards a manuscript, also on the basis of the book's binding.

Perhaps more significant is trying to understand the relevance of these two books for the personages of the Tornabuoni family. We know from other sources that there was a rich library in the family. Here we can only glimpse something of the kind when we read that: "In the study of the country house of Santo Stefano in Pane, there are 30 volumes of Latin and Vernacular books, unfortunately not better identified.

Instead, the Trionfi have a unique and prominent role. An example is present in both villas, and it is as if it had taken the place of a book of the Gospels, or of Dante. Ultimately, it is this unexpected role that gives all the information particular importance.

Florence, 07.28.2024