(by Michael S. Howard)

Franco has written a new note on processions, in this case that for the Palio in Siena, 1438. This translation originally appeared on Tarot History Forum at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1092&start=30#p17993, with discussion following. It seems to me to report a useful find, as I will explain in my comments following the translation--even if Franco himself does not find it so. The original, "1438: Siena – Dagli Angeli all’Amore", is at http://www.naibi.net/A/525-SIENCAR-Z.pdf, which appears in this blog as the entry for Dec. 7, 2016.

In translating this note, I have benefited from Franco's explanations of obscure words. In addition, there is one word that perhaps deserves additional explanation: "carro", Italian for "cart, wagon, float". For "chariot" there are other words; yet in English we would say "chariot" sometimes where Italians would say "carro", in the context of a cart, wagon, or float that we are in our imagination to think of in terms of those ancient Roman vehicles that at one time were used in war but by Greek and Roman times were reserved for the parades celebrating military triumphs--and perhaps for racing, if Ben Hur is to believed. I translate "carro" as "cart" when referring to the physical object, and "chariot" when referring to the object it is meant to represent, in the context of religion, myth, or military parades of the time. I recognize that the line between one and the other is not clear-cut, as in all likelihood the figures carried in religious processions were modeled on the military heroes in triumph, and vice versa. Comments in brackets are mine.

1438 Siena – From Angels to Love

(by Franco Pratesi)

1. Introduction

The origin of this study is unusual. Usually I take the initiative to carry out an investigation when I encounter something that seems to me worthy of investigation; any study then starts solely from personal initiative; if I continued to observe the procedure, I never could, nor would want, to undertake this study. It is something that has been stimulated by others, so that it also made me deviate from my usual route, centered mainly on Florence; but here we will move through the streets of Siena. There is also another significant step that contributes to the strangeness of this study: in some ways it can almost be considered an appendix to an earlier note on public processions (1), but the difference is not only that we pass from Florence to Siena: Only one triumph is being focused on, that of a single triumphal cart [carro], and the changes that it underwent over the years of our interest.

The thing is not trivial, because I personally am convinced that studies on one triumph are of little use for our primary purpose of reconstructing the appearance of triumphs among playing cards. In my opinion, one should seek the origin of the triumphal cards in a whole series of figures or episodes that may in fact occur in a sequence, such that one element follows another according to a ranking that is easy to identify. Thus this deviation is not so much from Florence to Siena, as from the search for triumphal sequences toward fixing attention toward just one single element, in this case the Triumph of Love. So I have to explain why I found myself in this unusual situation. I can justify myself with the convergence of two independent solicitations coming from two experts with whom I have been able to discuss related matters.

In chronological order the first of the two was Michael Howard, who has maintained on the web, and in private correspondence, that the introduction of a single triumph can provide useful information on the genesis of the Tarot. Based on the abundant literature of art history,

_____________

1. http://www.naibi.net/A/522-TRIONFICORTEI-Z.pdf

2

I could see that in Florence the fashion to introduce triumphal motifs in birth trays (2) and cassoni (3) was diffused after the introduction of triumphs in playing cards. However, if we are content with just one triumph, or a few elements of the genre, then something earlier can be found, and so Howard reported an example of a cassone of the 1430s (4). When, discussing together, he supported the importance of the contribution that could be derived even from individual elements, it was my idea that we should instead look for the entire series, to be able to extend the number of the six triumphs of Petrarch, while maintaining the presence of a clear hierarchy among the elements themselves.

At this point, however, came the second solicitation, independently. This time the responsibility goes to Paola Ventrone who, aware of my research, pointed me toward an old study of the history of the Palio of Siena, which has become the foundation of this note: Palio e contrade nella loro evoluzione storica [Palio and districts in their historical evolution], written by Giovanni Cecchini in the fifties of the last century and reproduced in an an important book dedicated to the Palio and its history (5). Like Howard, Ventrone also evidently judges that one triumphal cart can already provide useful guidance.

To convince me to check the information was precisely the coincidence, also in time, of the two solicitations mentioned: neither alone would put me on the move; to overcome my strong inertia one boost is not enough; it took two, simultaneous and unexpected.

2. The Chariot [carro] of the Angels

Everybody knows, more or less well, the Palio of Siena and there is no need for a new presentation; the whole Sienese citizenry is involved and has taken part in the event for centuries. In addition to the race true and proper, the connected ceremonies have always been of particular interest, and in particular the solemn procession in which, along a traditional route through the main streets of Siena, the highest civil and religious

_______________

2. http://www.naibi.net/A/511-DESCHI-Z.pdf

3. http://www.naibi.net/A/517-CASSONI-Z.pdf

4. viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1092&start=30#p18084

5. A. Falassi, G. Catoni, Palio. Milan 1982, pp. 309-357.

3

authorities marched, followed by groups of influential citizens, also representing the historical districts.

At the head of the procession normally advanced a cart on which was mounted the palio that would be awarded the winner of the race; it was a large banner [drappellone] of fine cloth, always different in detail, in more or less vivid colors, richly decorated. For us what matters here is the cart [carro] on which the palio was mounted and presented. The exact type of this cart is not known in detail, but it had specific characteristics, such that it was called the Chariot [carro] of the Angels.

The angels on the cart were real, depicted by a group of children appropriately dressed. These little angels who gave their name to the cart were not the main part. The most significant objects were in fact the same palio mounted on a high pole, which usually ended at the top with the silver statue of a lion, and a large statue of the Madonna. The fact that the angels would pass from being marginal elements of the scene to its protagonists came from an additional special feature: they were not stationary on the cart, but some mechanical contraption made them move up and down around the Madonna. In this way they actually became the focus of attention of all the observers.

From the documents cited by Cecchini for the years 1406 and 1407 we come to know various details, including expenditure for oranges to be distributed to these children.

Can we speak of triumphs in such events? Definitely not, because if a triumph is a statue of the Madonna carried in procession, one would have to conclude that triumphs were common and frequent for some timeWe see specified (...) that the palio was mounted on a painted pole “so as to serve as a kind of a flagpole on the cart” [“per penare in sul charro”, literally, "for pennanting on the cart"] and had a silver lion on top. This annotation confirms the fact that for some time the palio was carried around on the cart, which was thus the chariot of the Angels to which we have referred, that is, a machine whose armature held up the young people dressed as angels and made them go up and down around an image of the Madonna. And the cart mus have been now quite old, because on 17 August 1406 the Workman of the Cathedral was authorized to spend 10 florins to repair it according to the agreement made with a certain crossbowman named Christopher, as well as an expense of 36 soldi for oranges to give these little angels, certainly to console them for their uncomfortable position. (6)

__________

6. Ref. 5, p. 319.

4

in every town small and large and not only in Tuscany. So we will have to attend to the changes in this scene, so that it becomes of interest to us.

in every town small and large and not only in Tuscany. So we will have to attend to the changes in this scene, so that it becomes of interest to us.

3. The Chariot of Love

For the triumphs in playing cards, the earliest date that we know so far is 1440, but we have no precise guidelines on how far back we should still get back to the origin of the new cards. Possibly once it is acknowledged that going back is permissible and indeed desirable, the thirties are presented as the best candidates. The fact of the cart in Siena near the triumphs of our interest occurs just in the time where some of our hopes of finding useful documentation is concentrated: in those years of our interest there was in fact in Siena a major change for the triumphal chariot whose story we are following.

The details of this event, extraordinary even for us, are not known. The importance of that change mainly concerns the atmosphere that the cart evokes; from a technical and construction point of view, the change could require a notably reduced effort. But it is clear to everyone that a Charitot of Love may not have much in common with Our Lady and the angels around her. Now Petrarch had arrived and, above all, the Renaissance. If one looks for documentary testimony of the appearance of triumphal motifs before 1440, the triumph of love of Siena may be added to the few known cases, such as illuminations of the Triumph of Fame present in a few manuscripts.In 1438 the Workman of the Chamber was authorized to spend up to 16 lire "on the chariot of Love”. It was to be the new cart of the palio, and it is curious to see how it had gone from the old sacred chariot of the Angels to this, absolutely profane; the spirit of the Renaissance was also active in Siena, even in its most traditional and sacred festival.(7)

It should also be noted that the year 1438 of the title does not correspond to the first building of that cart, but only the first time that Cecchini finds it mentioned in the documents. The preserved records show that only five years earlier, when in 1443

_____________

7. Ref. 5, p. 321.

5

Siena was visited by Pope Eugenius IV and his court, the card needed to be replaced or at least repaired.

The motifs used on the Chariot of Love are not clear to us and we can imagine several alternative cases: perhaps the new cart was not built in a fairly solid manner, or by 1438 it had already been introduced and used for several years; we should look for other documents, if they exist.Because it was necessary to increase significantly the allocation of money for the festival, especially since he was also ordered to redo from scratch the cart for the palio, this that shows as the Chariot of Love, had to be, rather than a real cart, one of those allegorical machines, as became usual in the displays then ordered by the districts. However, this order was unable to be followed, because with hospital expenses, donations to the pope, sultan [the Eastern Emperor, Franco says] and cardinals, and provisions of grain to the population, the municipal coffers were empty, and therefore they had to be content brushing up the old cart.(8)

If we then go still further in years, in addition to the narrow time interval of interest to us, we again find something interesting, because it shows a reasonable connection with something similar happening at that time in Florence. Indeed, as we could imagine, we witness the greatest progress in making these special carts had been in Florence: in 1453 in Siena in fact it was decided that precisely from the Florentine progress could be taken the model for improving the quality of the Sienese cart.

Those who know the environment know that for Siena it was not easy, nor frequent, to recognize the superiority of any Florentine product; if it was admitted, it must certainly have been true.It was then ordered to completely redo the cart of the palio, and they were sent to Florence to see a model. The decoration, in gold, silver and German blue was executed by the painters Antonio Giusa and Antonio di ser Naddo, who received 100 florins in compensation. You see from this, not only how the decoration should be lavish, but also that the resolution of 1443 for the execution of a new cart had remained a dead letter, as often happened to many Sienese resolutions and laws. (9)

__________________

8. Ref. 5, p. 322.

9. Ref. 5, p. 322.

6

4. Personal Comment

Personally I am in an unusual position, one that is just strange. On the one hand, I sincerely hope that the information presented will be useful to some researchers to get closer to the solution of our problem, limited to the history of playing cards; on the other hand, of this utility I myself am not convinced. The oddity is due especially to being found in sharp contrast to the usual situation. Usually one can be convinced of the validity of a given hypothesis, but then has difficulty convincing the other. Here is rather an attempt to convince others of the validity of the information, without its meeting my criteria of not searching for a single triumph, but for a whole series. In practice, I "had to" write this note after two stimulations received simultaneously by two experts who judge, unlike me, that information of this kind can help to clarify the complex situation of the various historical reconstructions of the origin of the Tarot.

I have no doubts about the veracity of the information, because I know other studies by Giovanni Cecchi, which seem to me totally reliable. Possibly there would be found in the manuscripts of the Siena Archives of State, especially in the register of the Biccherna, clarifications on the date of the transformation of the Chariot from Angels to Love recorded here first in 1438, when it was already in effect, but perhaps going back to the beginning of the decade or even a bit earlier.

To explain the appearance of triumphs in playing cards (with the first notice of 1440 in Florence) events are sought with triumphal characteristics in other aspects of city life and artistic products; among these we find countless examples from around mid-century, but very few before that 1440. Here we recall one of Sienese origin.

For each occurrence of the Palio, the main festival of Siena, a cart was used to transport the new palio (on display, as in triumph) and a scene with figures, leading the solemn civic procession.

7

In the 1430s - or maybe even a few years before, but we have information only from 1438 - the Chariot of the Angels was exchanged for the Chariot of Love, that is, there occurred in that cart the transformation from a scene in which the Madonna appeared surrounded by moving angels to a scene in which the triumph of Love was shown, obviously very different.

Compared with the six triumphs of Petrarch, to have only one triumph represented here may appear to some - including myself - insufficient data. However, one cannot help but recognize that the change in atmosphere that occurred in Siena with the "small" change in the triumphal car was in reality enormous, in practice changing from the Middle Ages to the High Renaissance. On the other hand this triumph was not just any; it was the primary occasion in which the new palio, with all its honors, was presented to the citizens - the object that was most precious and most characteristic of the whole festival.

Franco Pratesi – 07.12.2016

Comments

(by Michael S. Howard)

I will try to explain my reasoning behind valuing the depiction of even one triumphal motif in the period before 1440 in cities known for having the tarot early on. (Siena counts, because its ordinance excluding triumphs as a prohibited game was passed in the same year as that of Florence, 1450.) From there I will go on to evaluating the significance of what Franco has presented in the note translated immediately above.

Franco says:

What we are looking for is, as Franco puts it elsewhere, “triumphal motifs”, a term that is at this point necessarily vague. But for him it is defined in terms of something that could give rise to the sequence of special cards in the tarot, then called trionfi....sono personalmente convinto che gli studi su un solo trionfo sono poco utili per il nostro scopo primario di ricostruire la comparsa dei trionfi fra le carte da gioco. Secondo me, si deve cercare l’origine delle carte trionfali in un’intera serie di figure o di episodi che, possibilmente, si presentino in una successione tale che un elemento ne segue un altro secondo una graduatoria facile da identificare.

(... I am personally convinced that studies on one triumph are of little use for our primary purpose of reconstructing the appearance of triumphs among playing cards. In my opinion, one should seek the origin of the triumphal cards in a whole series of figures or episodes that may in fact occur in a sequence, such that one element follows another according to a ranking that is easy to identify.)

It seems to me that there are two ways the interaction could go: triumphal scenes in other arts influencing the triumph sequence in playing cards, and vice versa, the playing cards influencing the choice of motifs in the other arts. If so, the term “triumphal motifs” becomes necessarily even vaguer, including effects as well as causes of such motifs in the cards.

I will deal with the former direction first, from what we are searching for to the cards. Let me be clear I do not expect that one triumphal motif in isolation, or even 22 such motifs in isolation from one another, would explain the playing card sequence, precisely because it is a sequence. It is the selection of motifs as a group in something like a particular order that must be explained. I agree that it is as an extension of the six triumphs of Petrarch that this probably occurred, and it would be nice to find such sequences in other media. But it may well be that the only such examples were precisely those of Petrarch and Boccaccio. For the rest, it is a matter of adding subjects drawn from other areas of life and art (art being defined broadly, as in “liberal arts”), stuck in where someone thinks it appropriate.

Whatever the truth, knowing how triumphal motifs in other arts were presented even in isolation is useful for understanding various aspects of the sequence’s history: for example, why the cards in one city look different from the cards of another city, if they draw from slightly different preexisting models. Perhaps the presence of certain details in a card can even locate the origin of that detail in a particular city, based on a similarity in other arts of that city, or the approximate dating of a corresponding card.

Also, it is not clear that in the particular cassone I had in mind for one triumph, that of Fame (http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-xlbf6GdiYPk/U ... anPL25.JPG), it is actually in isolation from other triumphs. In that cassone illustration, for example, we can find popes, as well as royalty of both sexes. So if “Pope” is a triumphal motif, loosely enough defined to include all or most of the tarot subjects, then there are at least two such motifs in one “triumph of fame”, more likely four (including Empress and Emperor).

Another example is a depiction of Apollo and Daphne (above), which the Courtauld Institute dates to c. 1430 (http://artuk.org/discover/artists/stefa ... i-14051483). Love, in the person of Cupid, is shown triumphing over Apollo, and Daphne, for the sake of her chastity, over Apollo. Here there are two triumphal motifs. Does this count as a predecessor of the tarot? (Never mind its relationship to the Marziano, which seems to have had the odd relationship of Apollo triumphing over both Daphne and Cupid; see chart at http://trionfi.com/olympic-gods.) For my postulated tarot-predecessor, there is even a Cupid above the couple, just as on every version of the card. Or is it simply a cassone illustrating an episode in Ovid? To answer this question, we need to look at the cassone in the context of other cassoni to see what the habitual mode of interpretation was, whether of love and chastity and the battle between them, or something else (assuming that in the tarot chastity=chariot, as it seems to in the Cary-Yale).

In actual fact, if we look at the stories, usually from Ovid or Boccaccio, that are illustrated in the cassoni of the period, we see many cases of love and chastity being at odds, and one or the other winning. One example is Boccaccio's Tesseida, on a cassone now in Stuttgart, c. 1425 (http://www.staatsgalerie.de/malereiundp ... g.php?id=3). Two men, one associated with Mars and the other with Venus (according to Paul Watson in Virtus and voluptas in cassone painting. Ph.D. Diss. Yale University, New Haven 1970) , are in love with the same woman, who of course is associated with Diana. The Martian interrupts the Venusian's wooing and challenges him to a duel; instead, they have a public trial by combat. Mars wins but dies of his wounds (thanks to Venus) soon after. So the Venusian gets the girl, whom he weds and beds (I am not sure on the order). It is the triumph of Venus over Mars, love over war, Venus over Diana, love over chastity.

Another example is Boccaccio's Ninfale Fiesoleano, in 3 surviving cassoni c. 1430. Diana is observed with her nymphs by a passing hunter, who falls in love instantly with one of the nymphs. Venus appears to him in a dream and promises him the nymph, if he will follow her. He catches the nymph by herself and proclaims his love for her. She throws her spear at him, but in so doing looks him in the eye and so is entranced by his beauty. Venus in a dream advises him to disguise himself as a nymph, join the band, and grab her when he has his chance. He does so, When the nymphs take off their clothes to bathe in a stream, his chance comes, and she yields. It is the victory of Venus over Diana. The nymph feels guilt for what she has done and rejects the young man. When Diana sees the ensuing child, she turns the nymph into a stream, in fact the very one that flows by the Villa I Tatti. Chastity is avenged. In this case, love's triumph was not within marriage, so the result is an unhappy one.

An example of the opposite type is that of Acteon and Diana. When he experiences lascivious pleasure at seeing her and her nymphs bathing, she turns him into her animal; it is the victory of Chastity over Desire. At the same time, the viewer enjoys the forbidden pleasure of seeing what Acteon saw.

There are other such examples. Even a simple "garden of love" is an example of chastity vs. love. The groom's party takes the bride from her house to the groom's in a triumphal procession. Her chastity is overcome by his love, but since it is sanctified by marriage it is also the setting for a victory of another kind of chastity, that of the married person, a chastity that dictates the faithfulness of the two to each other, a chastity that will be tested over time.

Another type of example, not of love and chastity but of other triumphal subjects featured in the tarot, is that manuscript illuminations of virtues shown triumphing over corresponding vices, although not triumphing over one other. Does that count as a predecessor of the corresponding tarot cards, assuming the order of the whole comes from elsewhere? I would not think that they would likely be an original basis for the tarot sequence, precisely because they do not form a sequence of one triumphing over another. That does not count against their being inserted into such a sequence with others that do fit the triumphing pattern, e.g.. the Petrarchan ones, in some order, such that their place in the order either has to be memorized by rote, or with a rationale, either taught to one or made up ad hoc by the player himself as an aid to the memory.

Of the John the Baptist processions in Florence, even if they do not show “our” themes, yet they influence how people saw sequences of images, i.e. a procession of banners with images of animals representing 4 districts in each of 4 quarters of the city gets people used to a 4x4 structure in a sequence. Seeing a series of floats illustrating key events in the Bible in temporal order gets people used to a sequence of triumphs as telling a story, even one with eschatological implications.

Such considerations can help us to see how a sequence, one that in its conceptual beginning may have had only 6 triumphal motifs strictly analogous allegorically to the idea of one card “triumphing over” others in a trick-taking game, could expand to 22, in which the allegorical motif of “triumphing over” the preceding one no longer holds in every case. It may be groups of cards triumphing over other groups of cards, or like in the Bible, where events succeed one another without “triumphing over” the preceding one, even though there are triumphs over preceding conditions along the way (e.g. the crucifixion as a triumph over “original sin”). In short, I do not see why there has to be an artifact such as what Franco is looking for, an expanded version of Petrarch’s 6 triumphs, in which each somehow “triumphs over” the one before. And if not, then anything reminiscent of some aspect of the sequence can reasonably considered of relevance.

Let me be clear that I do not consider a float in Siena, even leading their most important parade, of much relevance as part of the causal chain leading to the tarot sequence. It is simply a repetition of what is already in Petrarch’s and Boccaccio’s poems. The only bearing it could have would be as showing visiting craftsmen from Florence the popularity of the theme.

However that is not to say that such floats in general, before even 1406's Madonna and angels, play no part in the causal chain. Processions with saints are related in concept to processions with military heroes: both are elevated figures, physically as well as in importance, seen as playing important roles in the triumph over evil, whether civic or cosmic. Cards with saints are an important predecessor to cards with triumphs; saints are in fact triumphal figures whose effigies were frequently carried in processions. By themselves, of course, they are insufficient to bring about the cards we know as triumphal. But that there ever was some one thing that brought about those cards seems to me an unjustified assumption.

Now let me turn to the question of influence in the other direction, from the images on the cards to the other arts. Are the cassoni depictions of the six Petrarchan triumphs that start appearing in around 1440 or a little earlier reflections of the same themes in a new deck of playing cards? And if so, can we assume that since we only start seeing these motifs in c. 1440, that the game was not diffused in Florence before that date? Florentine craftsmen worked in a market economy where families vied with each other for the most prestige, and the minor arts are means of acquiring such prestige. The use of certain themes by leading families, even in playing cards, would be expected to evoke similar use on the part of other well to do families.

The problem is that the images on some of the cards do not correspond in spirit to the images in Petrarch or the illustrations to his poem. The Triumph of Love motif of Petrarch is that of people being made captive or slain by Love, shown tied by ropes or slain by his arrows. On the cards, what we see are examples of love as ennobling: a man on his knees before his beloved (see below) or bowing to her as they shake hands to seal the marriage vows (in the Cary-Yale and PMB decks of Milan). And in the cards there are no aloof young virgins who will not give in to love, but rather, in one motif, a male triumphator in condotiere garb, as though in a military parade, or holding a globe signifying the world. If it is a female charioteer, it is the prospective bride on the way to her wedding, or even after the wedding on her way to the groom's house. The groom himself is the groom of her horses. Likewise there is no card corresponding to Fame as a crowd of people surrounding a lady enclosed in a circle; nor is there an image of God or Christ in a mandorla. Instead, it is an actual world with hills and castles. On the cards, the images are either standard medieval images or else, in the case of Love and Chasitty, reflective of their conceptions as depicted in the period before 1440.

As I have tried to show, triumphal images of Love and Chastity are not unknown in pre-1440 Florentine birth trays and cassoni, in ways that, like the cards, reference a different concept than Petrarch's. Such examples count against the idea that such themes were not present in playing cards then. Yet these examples are unsatisfying: they are mostly not part of any tarot-like sequence; in many cases they derive from sources other than Petrarch’s and Boccaccio’s poems; and in many respects they do not resemble pictorially the cards they might be thought to have been inspired by. Their inspiration would just as likely have had nothing to do with the presence of the tarot at that time.

It is true that there seems to be a progress from Love to Death to Eternity in the cards of that time in Florence. If we see the Chariot and Virtue cards as representing Virtue = Chastity generalized, the Celestials as equaling Time, and Fame as expressed in the Tower card (as the Tower of Babel, made, the Vulgate said, to make its builders famous), the whole sequence could fit, after a fashion. So couldn't such a sequence, even if only partially paralleling that of Petrarch's, have been what got the cassoni going? The problem is that there was a change in theme among cassoni and the minor arts generally in Florence around that time, from scenes of sensuous pleasure to those of heroic deeds and its resulting fame: Jason recovering the Golden Fleece, the Greeks with their wooden horse, the Continence of Scipio and the Fall of Carthage, battles against Asian barbarians, martial or steadfastly self-sacrificing women. Petrarch's poem fits that change, which is the more likely cause of the interest in the poem and its resulting illustrations in the minor arts, not the tarot.

I am not sure how well the converse works. If there are examples of triumphal motifs reminiscent in some way, in imagery or concept, of the cards, does that mean that the cards were popular at that place and time? Not necessarily: the virtues that we see in the cards, for example, were in sculptures and reliefs everywhere for a long time before. Depictions of popes would no doubt have been in many places. Also, the themes of Love and Chastity were common enough among the literature read by the cultured elite of Florence.

But putting Love in place of the Madonna in Siena is a different order of magnitude. The palio procession is on the same level as public art, such as the images of the virtues seen in government buildings and churches. But Cupid did not have the same acceptance in church and publicart then in Siena as the virtues. For a triumph of love to be leading the most important procession in Siena, in place of a Madonna, something has indeed changed.

I am reminded of a local festival I once stumbled upon, back in the 1960s, in a small English village. The parade had plenty of people in traditional costume—bagpipers, Morris dancers and the like—but also four young men with electric guitars looking like the Beatles.

Are Boccaccio and Petrarch so popular in Siena of the 1430s that the presence of a motif from their poems is no surprise? Books are scarce, and so is literacy. If nothing else, Sienese pride might have mitigated against such Florentine inspiration, as Franco reminds us.

It might be that Siena, like Florence, had processions of people carrying cassoni in wedding processions, and that these cassoni had scenes depicting the triumph of love in such a way that it could be adapted to a float in a procession. But again, would such cassoni be such as to lead to the change from a Madonna to a triumph of love? Perhaps.

If the game of triumphs is popular, a game of which no one knew the origin (even then), then a triumph of love would be a festive nod to the crowd. Here is something you will recognize and of interest to all, it says; we are not all sanctity and reverence; there is also fun.

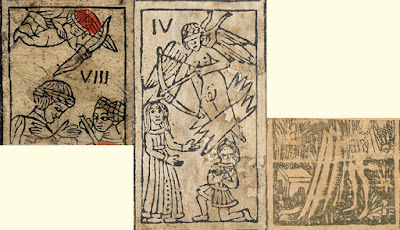

I imagine the card would have looked something like these (Metropolitan sheet, Rosenwald sheet, Cary sheet, Rothschild sheet), but we don’t really know.

(http://tarotwheel.net/history/the%20ind ... amore.html)

(http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105109607)

Unfortunately, we know even less about the “chariot of love” cart in Siena. One possibility is a young boy with wings and a bow and arrow, maybe in a state of undress, or flesh-colored tights, the palio above him and one or more couples below—not bound by ropes, but in loving poses. If so, the resemblance would be close enough. It would not be proof of the presence of the popular tarot in the town, but it at least be evidence in that direction.

On the other hand, if it is a young winged man with bow and arrows and with him on the same level a young maiden, then that comes from Boccaccio's Amorosa Visione, which describes the poet's beloved as "shining at Love's side" (dall'altro lato a Amor vidi lucia, XV.60). The same if it is a garden with loving couples and no Cupid. If it shows just Cupid at the top and below him people bound with ropes or slain, that is Petrarch ("some of them were but captives, some were slain"). If it is couples in a garden, that is a theme from cassoni, with nothing to do with the cards. If it has only a young lady on top, that too is not related to the tarot image; that would be Venus, as on a "triumph of Venus" birth tray of c. 1400 Florence. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Master_Taking_of_Tarento_-_Triumph_of_Venus_(Louvre).jpeg; dating from http://www.thecityreview.com/metital.html).

Given how little we know about this "chariot of love", whether it would be worth the effort to examine the records in Siena to see when this innovation came into effect I do not know. I expect that the author Franco was quoting from has already done that and not found anything. In any event, I am grateful to him for bringing this change in custom to our attention.

No comments:

Post a Comment