This is another essay pertaining to playing card production in Tuscany, focusing this time on the places where card games of various sorts were allowed to be played. The original, in Italian, is at https://www.naibi.net/A/LICENZE.pdf. The parts in brackets are mine, either after consultation with Franco or in relation to this blog format. This essay is also posted at https://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?p=26432#p26432.

Florence 1743-1778: Licenses for games

Franco Pratesi

Introduction

In past years I had the opportunity to study various registers of the Camera e Auditore fiscale

(Chamber and Fiscal Auditor) collection of the State Archives of

Florence (ASFi) and obtained quite interesting information from them.

However, there were two in the series of registers that I was unable to

use, also because the data seemed too confusing and irregular. These are

registers No. 3017 and 3018 relating exclusively to the registration of

revenues for the granting of licenses for the playing of games The

first (A) concerns the years 1743-1763, the second (B) the years

1763-1778.

Now I have resumed my study, in particular because I found information

about it in an important book on games in Tuscany in the eighteenth

century. [note 1]

In this academic monograph, Addobbati delves into the whole topic in a

decidedly above-average manner, also based on ASFi documents, including

the two registers that I am examining here. Indeed, Addobbati dedicates

an entire chapter of his book to licenses for games, pp. 165-194. Anyone

with an interest in deepening their knowledge of the topic will be able

to find in that discussion a valid reconstruction of the environment,

both in general and with some in-depth analysis of particular events and

personages.

In my study, I have limited myself to examining the records relating

to card games and reproducing a part of them at the end in the form of

tables.

Innovations of the Habsburg-Lorraines

The Habsburg-Lorraine dukes found in Florence a state that had

remained centuries behind. By now entrepreneurial activity, which

centuries earlier had made Florence a world-class capital, had been

replaced mainly by conservative agricultural ownership, in the hands of

the main families and the clergy.

As regards the limited sector of our interest, games, the Medici had

already tried on several occasions to put a stop to gambling, but in the

eighteenth century the situation was getting out of control. Many

people complained about dangerous losses of money, with understandable

negative consequences, and alongside the usual reprimands from the

clergy there were even pleas from entrepreneurs who witnessed the

serious losses, if not downright ruin, of their employees, especially in

the frequent case of young people, beginners with work and wages.

The traditional system of the Medici dynasty of granting exemptions

and privileges in a chaotic manner in response to individual requests

received, without precise rules and in any case without the concrete

possibility of obtaining rigorous compliance with any rule, contributed

to making the situation uncontrollable.

The Lorraine grand dukes committed themselves for several generations

to reforming the entire administration until the famous Leopoldine

reforms, which finally gave new life to the Tuscan state; in particular,

they immediately set out to combat gambling, trying to set precise

rules and limits. Only indicated games could be played and only in

places with a new license, granted upon payment of the relevant fee.

The process of combating gambling occurred in several stages and

ended, at least formally, with the law of 1773, which prohibited card

games everywhere, with rare exceptions, such as the Casini dei Nobili, which were formed in Florence and in the main Tuscan cities (those so-called nobili, noble cities - in which alone some of the main local families could obtain recognition of nobility).

___________________

1. A. Addobbati, La festa e il gioco nella Toscana del Settecento, Pisa 2002.

2

The contrast on the part of the revenue offices

All state administration offices were required, one might say by

definition, to follow any direction of the grand dukes. A nod, a barely

perceptible indication, was enough for the whole machine to start

spinning at full speed. Maybe this was indeed the rule, but not for card

games.

In recent centuries the money in the coffers of the Tuscan Grand Duchy

available for administration was increasingly reduced. In the specific

case of the department of playing cards, revenue from taxes on games was

an indispensable source for the very life of the office. Thus, in the

official correspondence studied by Addobbati, we encounter unexpected

clashes between the rigor proposed from above and the more permissive

attitude of the offices, which would have looked favorably on the

authorization of games such as the infamous bambara, for the evident

reason that the related tax brought much more money into the office s

coffers. Naturally, the result of the prolonged consultations could not

end otherwise than with a decision dictated by the Grand Duke, but this

only happened after an initial restraining action on the part of the

offices.

The accounting units used

In examining these registers, an initial difficulty we encounter is

that all taxes are indicated with a more extensive accounting system

than usual: we were used to the LSd system with 1 lira equal to twenty

soldi and one soldo equal to twelve denari. This system is also

preserved here, but with a larger preceding unit, the scudo (sometimes

also called ducat), worth seven lire.

I don't know the origin of this system, but at least two advantages

can be seen to compensate for the greater complexity: the first is to

reduce the size of the calculation, in the sense that 6 scudi are

expressed with fewer numerals than 42 lire, and this can be useful to

facilitate calculations in the case of large amounts. Even more useful

is the fact that so expanded this system can facilitate the divisibility

of the total amounts calculated into equal parts. The decimal system,

for example, involves digits that are not divisible into exactly three

parts, a drawback already overcome in the LSd system, but with scudi,

perfect divisibility extends even with a divisor of 7; I don't know of

any accounting system more "suitable" for this purpose.

The variety of taxes paid is quite surprising. The figures that are

most often encountered, especially within Florence, are 6 scudi for

minchiate and 17.3.10.- for low cards [ordinary 40 card decks]. The

frequent appearance of a complex figure like the last one already seems a

bit strange, and in fact the annual fee for low cards was double,

precisely 35 scudi, a round figure like the others. In some cases, the

annual tax was simply paid in two installments, but Addobbati suggests

that many shopkeepers paid only one semester [six-month period], when

there was more crowding at the tables, and in the other they did not

hold games, or held them secretly.

Furthermore, especially when leaving the city of Florence, taxes were

reduced in several ways. This occurred partly due to a generalized

reduction and partly due to the maintenance of ancient privileges which

were left to the negotiation of individual cases.

The changes over the years

Leafing through the registers we find unexpected differences from one

year to the next. Especially at the beginning, the procedure was clearly

being fine-tuned and the problem of the game of bambara had not yet

been resolved. In fact, there were two different fees for the low card

game license, one with bambara and one without. A few months later,

bambara was included among the prohibited games and for a while, again

in the license for low card games, it was specified that it was not

included.

Next, for the permitted low card games, is the general formula of

"deal games" [games in which all or most of the cards are dealt out

-given to the players, mostly of the trick-taking variety]. For the

territories of Livorno and Pisa, it is preferable to introduce a

contract with concession holders who, for an agreed annual sum, deal

with the granting and control of licenses and collect the amounts.

Indeed, at a certain point this system ended up being extended to the

whole of Tuscany, typically in the year 1751 (see relevant table at the

end), but the result was not encouraging, and the traditional system was

soon resumed.

3

For the Tuscan bureaucracy, 1750 is a very important year, involving

all the registers and account books of the administration. In fact, in

Tuscany the law changes the beginning of the year to "our" January 1st

instead of the traditional March 25th. In these registers, we thus also

witness clear innovations. The first months of the year, from January

1st to March 25th, now have the same year number as the following months

and no longer that of the previous ones. However, for several years,

the final annual balance sheet continues to be set at the end of

February.

Of all the variations that we encounter from one year to the next, the

most impressive is the one that we read in the second of the two

registers, the one marked B. In fact, inside it, we go through the

"revolution" with the victory of the rigorous approach towards games of

cards, as commented below.

Annual budgets

These books are kept as revenue journals, and hence the taxes

collected are recorded on the same day of payment. (For simplicity, in

the tables added at the end I limit myself to transcribing only the

month.) However, each year the final account is entered for the entire

previous year. This happens with a few summary lines after the income

for the month of February, and this continues until 1776, despite the

fact that from 1750, the new year begins as today, from the first of

January. In 1776 the budget relating only to the last ten months was

reported, in order to match the new limit of the year. The last entry is

from March 1778 and is calculated only for the first three months of

that year.

We have glimpsed that there were notable changes in the laws on games

during that period; correspondingly, it is natural to expect a clear

change in revenue corresponding to the taxes for the related licenses.

However, if you look at the following table and graph, compiled with

data from the registers, the conclusion is rather unexpected. The dotted

line in the graph interpolates the data and actually indicates a

general decrease, but a small one, much less than we would have

expected. In the following data, no sudden changes, and in particular no

permanent decreases, are observed either; at most there were individual

deviations from the average values which were then quickly reduced in

subsequent years. Perhaps there was also some compensation between the

increasing number of licenses and the decreasing individual tax. [For a larger and clearer version of this and other tables here, click on the link below them.]

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=3042

4

Information on games

We need to reflect for a moment on the games and players of the time.

On the games that were played, we actually don't get much from the

licenses. There were games of chance that were always prohibited -

already in the time of the Medici - such as bassetta, pharaoh, and

thirty-one, but these, too, were probably widespread because many game

rooms were in practice inaccessible to controls. The extreme case,

however, at that time was that of bambara, a game that derived from

primiera (and which can roughly be considered an ancestor of poker),

which created problems because it was the favorite game in every club,

or at least it would have been if they had allowed it.

From what we can glean from various testimonies, we could immediately

conclude that playing cards were preferentially used for games of

chance. The complaints were especially against young gamblers who

preferred fast games of chance. Bambara was understandably the most

popular game; when it was decided to ban it, buia [current meaning =

dark] was introduced, a variant that was only different enough so that

its name was not present among those of the prohibited games.

It was not easy to distinguish between pastime games and gambling,

especially when using low cards. Could you play pastime games of the

minchiate type also with low cards? Certainly yes, and in fact in the

early years, deal games were spoken of, and among these, tressette

explicitly appeared, albeit rarely.

However, making sure that players used low cards only for permitted

games and not for prohibited ones would have required control that was

impossible due to the limited number of agents and the frequent

possibility of bribing them so as not to be reported.

Minchiate

The oldest and most traditional game was naturally that of minchiate,

which was played in cafes, but also in barber shops, and specialty

shops [apothecaries, spices sellers], and private homes. In itself, it

is a game very suitable for spending an afternoon or evening in the

company of friends and acquaintances. The game is slow, requires

reflection and patience, and is therefore suitable for older people with

sufficient free time available. These characteristics merited the

recognition of a considerably lower license fee, typically only six

scudi instead of thirty-five, and even less if the venue was located

outside the city.

However, we have a sort of demonstration of the preference of the

Tuscans of the time for games of chance, starting from the same

minchiate. Why did minchiate have preferential taxation? Because it was

the most traditional deal game : this typology could also be present

when playing with low cards, but in contrast to all the others,

minchiate had the advantage of a single deck associated with that

traditional game and not those of games of chance. With all those cards,

you couldn't play basset or pharaoh!

However, the situation was not that simple. In particular, it can be

assumed that gambling was also done with minchiate; indeed one can even

think that at the time minchiate was used preferably to save on the

license fee, while still allowing players to practice some new games of

chance to their taste. No agent could claim to find players engaged in a

game of chance if they had the typical minchiate cards in his hand.

There may have been many cases, but a precise testimony was preserved

for us by Biscioni who in the additions to Minucci's notes to the Malmantile Reacquired [note 2]

even gives us the rules of a couple of games of chance played with

minchiate. Michael Dummett includes them among the games of his

monumental book,[note 3] while

they are judged to be so extraneous to the general characteristics of

tarot games that in the re-edition with John McLeod they are only

present in an Appendix to the second volume. [note 4]

________________________

2. (L. Lippi) Il Malmantile racquistato di Perlone Zipoli colle note di Puccio Lamoni e d’altri, Firenze 1731.

3. M. Dummett, The Game of Tarot, London 1980, pp. 353-354.

4. M. Dummett, J. McLeod, A History of Games Played with the Tarot Pack, Lewiston 2004, vol. 2, pp. 848-850.

5

The inventiveness and cunning of Florentine players were truly

uncontrollable. How could any tax or police officer have recognized, for

example, a sequence counted again for the score at the end of a

traditional game from an identical sequence used as a combination in a

poker-like gambling game? Not only the same unique cards, but even the

same combination. So you could gamble in complete safety.

Other games

Probably in each individual license the various permitted games were

listed; in the register in question, reference is always made to the

license for the details, necessarily omitted from the summary

registration of the day.

For example, the game of chess is perhaps only written on one

occasion, but we certainly cannot consider it a forbidden game. Among

the games of this genre, checkers never appears, although it must have

had a certain following (at least in barber shops, and I am old enough

to have a personal memory of this from the mid-twentieth century, when

minchiate had been forgotten, even the name).

At the other extreme, among the games of chance, a sideshow game also

appears. The case is very unusual, because it does not involve a cafe or

similar establishment, but a type of traveling attraction which had

previously required special authorization from the Fiscal Auditor

himself. On 9 August 1847, Mr. Domenico Cocchi paid 100 L (14.2.-.-

scudi) to allow the public to play Girello, also called Alla bianca e alla rossa

- To the white and to the red - "but outside this city of Florence".

Without knowing it in detail, I imagine that it was a primitive kind of

roulette, which could be transported from one fair to another.

The places of games

The first substantial distinction between the places where the license

for games was granted is between the premises within the Florentine

walls and other locations. Inside the city, the rates were relatively

uniform with few exceptions to the usual rates of 6 scudi for minchiate

and 35 for low cards. The higher fee appears almost exclusively as a

half-payment, whether the entire fee was paid in two parts or only the

part relating to one six-month period. Leaving Florence, the fees

usually appear lower and less regular, with fluctuations that are

difficult to understand. Each license contained the precise terms of the

concession, and therefore it is possible that there were also

differences in the games allowed or otherwise, but in the registers,

only "according to the license" is regularly seen, and no additional

conditions are reported.

Various licenses were granted for nearby locations, such as Peretola,

Campi, Settignano, Baccano (a miniscule village just above Fiesole). It

is easy to imagine that in such places local players gathered with some

stranger, such as a city-dweller on holiday or a professional in full

"working" activity, with the intention of making large profits at the

expense of people less expert in the tricks of the trade.

In the smaller Tuscan towns, compared to what we might suppose, some

appear and others do not, without an apparent criterion of regular

geographical distribution, up to the Tuscan Romagna, almost touching the

Adriatic. Then arriving at the larger cities, we can notice the absence

of Siena, but we know that in that area, control over games was

reserved by ancient tradition to the local Casino dei Nobili. However,

for Pisa, and especially for Livorno, we find few licenses registered

because in those two territories, there were contractors who paid an

annual fee to the tax authorities and directly collected the fees for

the licenses they had the right to grant. This delegation of the

granting of licenses was sometimes also present in occasional cases, as

happened in 1761 for the Prato Academy when, as a counterpart to the fee

paid, it was in turn able to grant two minchiate game licenses.

The second register, No. 3018 or B

At the beginning of the second register, there are situations quite

similar to those of the first for a few years; however, shortly after,

the situation changes profoundly: card games appear only as

6

very rare exceptions, while now the rule is to grant licenses for

billiards, trucco, and other similar games, among which the spinning top

is sometimes found mentioned. At the end, I have only reported the year

1774 in table form, but it can be considered representative of a

situation that also occurred in a similar way in nearby years.

We have a lot of information about the technique and diffusion of

billiards, but trucco has been completely forgotten for many decades. It

was a kind of billiards in which, however, the balls were pushed by

long mallets along certain paths on the table, with rings to cross and

obstacles to overcome, which could recall similar games played on a

larger scale on the ground, outdoors. The spinning top, on the other

hand, is better known as an outdoor game for children. I don't know how

it was played inside. The potential game possibilities vary between wide

limits. At one extreme, a game of skill: two players compete to see who

can make the rotation of their top last the longest. At the other

extreme, one uses a multifaceted spinning top with its facets marked

with numbers or colors and bets which one will land on at the end. The

second type would seem to be the one favored by Tuscan gamblers of the

time, but as a game of chance, it would have been prohibited.

Since there is almost no more information on playing cards, from our

point of view this data could be completely overlooked. In addition to

the rare cases of card game licenses, however, there is other useful

information. Meanwhile, it can be verified that those who ask for the

license are often the same cafes and various venues that requested it

for card games. But there are some necessarily different aspects,

including one of some interest, already indicated by Addobbati in his

book. Mainly, it is not possible that all players who usually played

cards would find the same possibility with the "new" games. If

previously twenty people played cards on multiple tables in a room, now

only two or four typically play billiards. What do the other

sixteen-eighteen do? Are they just watching? Certainly not: they bet on

the outcome of the current match, and they even commit large sums to

this. So it was always gambling that won.

Florence, 01.20.2024

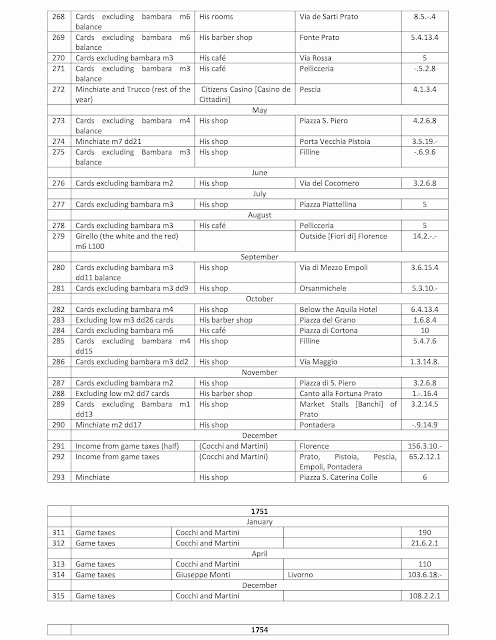

TABLES

Introduction

In selecting the years to summarize in the final tables, I based

myself on a few series of subsequent years and chose other single years

that seemed more representative to me. I have always set the limits from

January to December, and until 1750 I did not respect the old numbering

of the years (for the months from January to March). Instead, I have

kept the spelling of the names of the places, even when they appear

unusual today, such as reading, for example, Ponteadera or Pontadera for

Pontedera. In some cases, we come across slightly curious spellings,

but closer to popular pronunciation, such as Domo next to Duomo, and

similar. With rare exceptions, I have not written down the name of the

person who obtains the license, nor that of whoever eventually goes to

make the payment on his behalf.

When I report the numerical data of the amounts paid, if it is a whole

number of scudi I do not usually indicate the following zeros, i.e., I

write for example 6 instead of 6.0.0.0, or, as more usual , 6.-.-. -.

The tendency for these taxes is precisely to be based on whole numbers

of scudi. When non-integer values are encountered, an explanation is

usually also found: either it is half the tax, typically 17.3.10.-, half

of 35, or it is a balance after a fractional down payment, or it is for

other reasons that usually are reported explicitly in the register.

Often these are adjustments (and therefore I add "adjustment" in the

tables), such as the payment of a higher tax deducting what has already

been paid for the lower tax. In 1747, there are figures that must be

calculated differently from day to day, depending on the time remaining

before the deadline, and in this regard it is easy to imagine that the

assistance of an expert accountant was indispensable.

When only the address or name of the shop is found without indicating

the city, it always means that it is Florence, in the registers tacitly

understood. [Here m means month or months; dd - originally gg - means

days, the time remaining for which the license is valid.]

7

[For a clearer view of this table, go to https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=3043. Similar links are provided for the other tables here.]

8

9

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=304510

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=304711

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=304612

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=304813

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=305514

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=3059

15

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=3058

16

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=305217

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=3057

18

https://forum.tarothistory.com/download/file.php?id=3054

No comments:

Post a Comment