This post presents a translation of Franco’s "Firenze nel Seicento ‒ Ottave sul Gioco dell’Ombre," posted April 17, 2024, at https://www.naibi.net/A/OMBRE.pdf. It transcribes and discusses a poem about an offshoot from tarocchi known as Ombre, from the Spanish "Hombre," meaning "Man." The poem that Franco found describes the action that ensues, in this case in a game for five players, long since defunct, called quintilio in its Italian version. The players here are all women, while men attending them - called "Zerbini" in the poem, a term for elegant and proud young dandies, from a character in Ariosto's Orlando Furioso - make comments intended to impress. Whether these are whispered or audible to all is not said.

Translating this work poses particular problems in that the rules for this game are not precisely known, nor the precise meanings of some of the particular technical terms used in the poem. So several terms will be left untranslated, although with some suggestions in brackets, mine in consultation with Franco. This is a rather unsettling result. Understanding these terms, moreover, would seem to require knowing a little about the game. Franco gives the bare bones in his note, but I think more is required, albeit at the risk of introducing confusion: in particular, what happens in the game at the end of the hand.For tarot history, the significance of ombre is threefold. First, it is a continuation of the trend, apparently initiated in Spain, to apply tarot’s idea of trumps to the ordinary deck, in this Italian case of 40 cards. In hombre, called ombre in Italy, one of the ordinary four suits is made trumps, chosen by the player who wins an auction at the beginning of play. (In addition, there are a few permanent trumps - actually even more powerful than ordinary trumps, because they do not have to be played if one is out of the suit led.) It is the earliest known game to have such bidding, in a development that included even a variant of tarocchi, the so-called "tarock-l'hombre." The different bids in ombre need not concern us, except that there is more than one, so one player can outbid another. There are different technical terms for bidding. In the poem, we see “gioco” – I play - and “pongo” - I put - the latter certainly a bidding term, the first possibly.

The bid, among other things, is to win the hand. In all versions of the game, the winning bidder is called the “hombre” or “ombre” – the man. In the five-person game, he/she chooses a partner (see English wikipedia on Ombre); it is their combined number of tricks won that matters, according to the 17th century booklets. There are 8 tricks. How many must the pair win? 5 certainly will win. But is 4 ruled out, if none of the other players get more than 3 tricks each? It depends on whether the team has to win a majority of the tricks or just more than any other player individually. In the three-person game in English sources, it is the latter. English Wikipedia says that in the five-person game, five tricks were necessary; but the source it cites (Parlett) says nothing on this issue. For understanding the poem, the precise number is not important. What matters is what the win is called. In the three-person game, as described on Wikipedia, the win is called sacada, Spanish for “pulled.” Sacada is not used in the poem. However, there is the term tirar, which in Italian means “pull," and the context in the poem seems to fit winning.

Then there are the types of losses. Unfortunately, I have not found any source for the five-person game's terminology except the poem itself. In the three-person game, the ombre can lose in two ways. If an individual opponent of the ombre wins more tricks than the ombre – or is it a majority of the tricks? - he/she wins by codille (in French). A majority would be 5; but 4 tricks would be enough if the rule is that he has to be the high scorer, if he had 4, the ombre had 3 or less, and the other player had one. Codiglio is mentioned by our poem, so that type of win by an opponent of the ombre partners existed in the five-person game. But what was it? I don't know; but surely it involved beating the ombre partners in some way. In a five-person game, winning 5 tricks out of 8 surely beats the ombre, but would that 5 a combined total of the three other players, or one player individually? Or is it that one player individually has only to win more tricks than the ombre and his partner? If those two played a really bad game, that might be easy to do. But might 4 tricks by one player be enough? Again, it doesn't matter; what matters is that the game ends with a winner other than the ombre partnership.

The second type of loss is that called the “puesta” – Spanish for put - or, in an English text of 1660, the “repuesta” – Spanish for “put again” or “put back.” In French the term seems to have been "remise." That outcome is when there is neither of the other two. So in the five-person game, if the ombre and partner win 4 tricks and the others combined won 4, that might be the “repuesta.” Or if they won 3 and nobody else more than 3, that might count. What probably applies, in the three-person game and quite extendable to the five-person, is that in this case the penalty is that the ombre and his partner have to put in the same amount into the pot as is already there, and it stays there until someone wins it in another hand; so the amount in the pot has been “put again.” In the poem, neither “puesta” nor “repuesto” is used, but there is the term “riporre,” which in Italian has the past participle “riposto.” I think that "riporre" is the poem's name for this type of loss; Pratesi, more cautiously, does not commit himself, as what is meant might be something else, given that besides "put again," the term has other meanings, such as "put back" and "lay down."

My sources: The Royal Game of Ombre, 1660, p. 6 in archive.org; English Wikipedia on Ombre; David Parlett, https://www.parlettgames.uk/histocs/ombre.html and The Oxford History of Card Games, pp. 197-199 in archive.org; and Thierry Depaulis, "Un peu de lumiére sur l'Hombre (3)" The Playing-Card 16, nos.1-2 (Aug.-Nov. 1987), p. 51. I do not think that the 1660 work has been generally available very long: it is only mentioned by Depaulis (part 1 of his essay, Playing-Card 15, no. 4, p. 109, note 13) and Parlett as a lost work referred to by Chatto; from whatever source, it was put on archive.org on Nov. 15, 2023.) I have not read thoroughly all of Depaulis's three-part essay, so please correct me if I have left out anything important. For "remise" as a doubling of the pot, applied to a different game but said there to derive from ombre, there is also John McLeod, "Rules of Games - No. 5, REVERSIS," The Playing-Card 5, No. 4 (May-June 1977), pp. 32-35.

With that introduction, I give you Franco, who will say more about the game.

Florence in the seventeenth century: Octaves on the Game of Ombre

Franco Pratesi

1. Introduction

I transcribe and comment on a sixteen-octave poetic composition on the game of ombre, as the game of hombre - of Spanish origin but widespread throughout Europe, especially during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries - was indicated in Florence. It is found in a voluminous manuscript collection of poems preserved in the Moreniana Library. [note 1]

The gaming environment that we find illustrated here does not appear surprising once we have various pieces of information about it from the literature of eighteenth-century narrators, and in particular from the numerous foreign travelers who crossed Italy for their historical and, above all, artistic education. However, the version of the game indicated and, even more so, the other compositions in the same manuscript, rather indicate an earlier dating, which remains uncertain but would be better placed in the middle of the seventeenth century. This is confirmed by archivists who already reported the manuscript as follows.

N. 311. Paper, XVII century, mm. 205x145. Pp. 517. Pp. . . . are blank. The notebooks of various numbers of pages that make up this codex are written by various seventeenth-century hands, except for the quad. [quaderno: notebook, but here a file or folder] formed by pp. . . . which are perhaps writings from the end of the 16th century. . . . Modern binding in ½ leather.

XXX - 15. All’Ombre in quinto giocar sol le donne [At Ombre in five only women play] (482a - 485b ). The Game of Ombre. Octaves.

2. Essential literature on the game of ombre

A fundamental study on hombre, and on its history in particular, was published by Thierry Depaulis; [note 2]

for the development of the game throughout Europe and for the related

literature I can refer to that work. A concise presentation can be found

in a book by Giampaolo Dossena with rules and historical notes [note 3]. More details, including its variants and their diffusion, have been provided by David Parlett. [note 4]

Rule booklets on the game were also printed in Florence; in particular, the well-known Bibliografia [Bibliography] of Lensi [note 5] lists

three editions of a manual dedicated only to ombre. The related dates

are in fact later than the poem under examination here, and quintilio

[the five-handed version] is not discussed (at least in the first

edition), but I think it is useful to talk about it to complete the

framework of reference.

Of the first edition of 1807, of twenty pages, I have found only one

copy, in the Classense Library, and not even this one is present in OPAC

SBN. [note 6] Surprisingly, at least

for me, I have not found any copy of the reprint of the same year, with

a few pages more; however, I am not surprised by the fact that I did

not find the third edition of 1852, because Lensi himself had only

noticed it as an indication from a bookseller's catalog.

As evidence of the coexistence of ombre with calabresella, we can

cite another Florentine booklet from 1822, which was in fact dedicated

to calabresella, or terziglio, but with Chapter X devoted to “Ombe

calabresellate,” a variant introduced in the Rooms of the Theatre of the

Cocomero. [note 7] It would seem to be a less rare edition, given that three copies are reported in the Nazionale

__________________

1. Biblioteca Moreniana, Moreni N. 311, at ff. 482-486.

2. Th. Depaulis, The Playing-Card, Vol. XV, No. 4 1987, pp. 101-110, and Vol XVI, No. 1 1987, pp. 10-18 [and 44-53].

3. G. Dossena, Giochi di carte internazionali. Milan 1984.

4. D. Parlett, The Oxford Guide to Card Games. Oxford 1990.

5. A. Lensi, Bibliografia italiana di giuochi di carte. Florence 1892. Reprint: Ravenna 1985.

6. https://scoprirete.bibliotecheromagna.i ... RAV1291600

7. Trattato del giuoco calabresella e ombre calabresellate diviso in capitoli. First edition. Florence 1822. Pp. 70+12.

Page 2

Centrale and Laurentian libraries in Florence, and in the Library of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana in Rome.

3. Elements of the game

In a nutshell, it can be observed that the game was born in Spain as a

game for four players called hombre, soon to give rise to variants for

three players, renegado, and for five, quintilio.

Renegado replaced the original game everywhere, maintaining, however,

except in Spain itself, the old name of hombre or its derivatives. In

Florence, but also in other European cities and states, over time it was

first accompanied and then replaced by tressette for three players, or

calabresella, and then definitively by the transition to four-player

games in pairs, with the same tressette and then with whist, which

followed one another in the fashion of the players.

Ombre was typically a game for three players, and there were

specially built triangular tables. One of the interesting aspects of the

game is the evaluation of what conditions are acceptable for playing

alone against the other two, depending on the cards received with the

distribution of nine cards. There are also various possibilities of

drawing or not from the group of thirteen cards left undistributed.

The game is characterized by rather complicated conventions on the

value of trick-taking cards in the various suits, which vary depending

on the trump suit. The complexity already begins with the three major

cards, the mattatori: the highest, the spadiglia, is always the ace of spades, whatever the trump suit; the second, the maniglia, is the 2 of trumps for batons and swords, or the 7 of trumps for cups and coins; the third, the basto,

is always the ace of batons. A consequence is that the fourth card in

the order of tricks can be the ace of trumps only for cups and coins,

before using the descending sequence of face cards and numeral cards for

all suits (with the exception of the low cards of cups and coins for

which the trick-taking order decreases from 2 to 6).

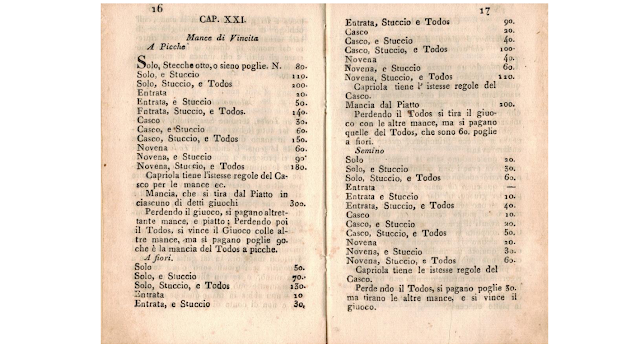

To give an idea of the complexity of the scores and related wins and

losses. I reproduce the two summary pages from the Florentine book of

1807.

8. From: Regole generali per il giuoco dell’ombre. Florence 1807.

Page 3

However, since the octaves in question talk about the game with five, I reproduce what has already been copied in the study cited by Depaulis from a very old Italian book. [note 9]

Another way of playing with five [players] has also been introduced, but it is called quintilio, that is, all the cards in the deck are taken [distributed], eight for each, with the ability to buy the right of the partner's hand [?], and also the ability for one, who wishes to play and become Ombre, to call as his assistant and companion one of the other four, who cannot refuse the invitation.

In short, the game was normally played

with two against three, but in cases of particularly favorable

distributions, it could also be played with one against four. There was a

ranking of commitments to control the game, so that a second player

could take on the more onerous commitments and thus acquire the right to

set the trump and name his partner.

4. The text

I reproduce a detail of the poem and then transcribe it in full below.

Biblioteca Moreniana, Moreni N.

311, XXX, 15, pp. 482-485. Detail.

(Reproduction prohibited)

9. Del giuoco dell’ombre con alcune osservazioni aggiunte. Rome 1674. [Depaulis quotes it on p. 51 of the third part of his three-part article cited in n. 2]

Page 4

Page 51

At ombre in five [note 10] only the Women play

in private and public feasts and to

satisfy their greedy desires;

Cavalier Zerbini [elegant and ostentatious young men, so-called from a character in Ariosto] stand above them.

On each trick a rigorous examination

these are wont to make, with three thousand bows;

many there are, to take away that taste [for the game?],

who more than once make them riporre [literally “put back,” technical game term].

________

Note 10, to stanza 1. Quintilio was evidently still in fashion.

2

Ombre is a beloved and delightful game

that comes from Spain, and in France is used

and also in Italy little by little;

but here in particular, it has expanded,

so that there is no casino, no redoubt, no place,

where one plays, where it is not played;

and there is no lady, whether ugly or old,

who does not take it for her game every hour.

3

At first this game seems a little difficult

for a girl, or rather a wife;

but if she begins to take it and enjoy it,

only when she plays does she find rest and peace,

more indeed than a husband makes grumbling,

if in supporting his wife in such a thing

he ruins his estate, and he languishes afflicted

if she sucks from him his most perfect blood.

4

Then if it happens that she loses every evening,

it's up to her husband to fill her purse,

nor can he contradict her with a proud face

if he loves her at all, or if she also is beautiful.

Indeed, nowadays the Woman is so haughty

that if her husband rebels against her in

this matter, she sells the best she has with great advantage

whether to the one who takes her arm, or to the Pedant, or to the Page.

5

But to get back to the game; The one whose turn it is

to deal the cards then deals only eight;

This must be done from above [from the top of the deck], and she won't accept it

if she notices anyone ever from below.

One who has the hand with a tight mouth

observes her game without making a fuss,

and If she has not long [in the suit she would choose as trumps?] as she would like,

she makes various faces, and then says, pongo [technical term: usually “I put” outside the game].

6

So the others follow. and there is one

who tells the knight [Cavalier] who stands above,

So much it is I want to test my fortune,

Perhaps [chissà, or who knows that, chi sa] the dice to my favor reveal

Slowly; he answers, there is no trick;

to dare, she says, here the knowledge is used;

it is enough that riporlo [technical term] doesn't seem strange to her,

he adds, while she has codiglio [technical term: ombre opponent’s/opponents’ winning hand/hands] in her hand.

7

She takes the die [singular of dice] and then boldly adds,

Ladies, to you I throw the stone;

the lady who sees must give help;

she says ironically, she's also polite,

I have the sheet there; and she incites

the Cavalier, to whom the blame is given,

to apologize; that one [he] replies, I advised you in vain,

I have nothing to do if you throw stones into the Arno.

8

If it is her turn to give to the one who helps her,

if she has that suit, she trumps in her face [in front of her].

If the other one, who claims to be astute

sees the higher [card] in the hunt beaten,

some dispute always arises between them,

so that more than one Zerbino quickly tries

to get in the middle, and with his

proofs to make both of them remain appeased.

9

There is one who hears from the Zerbino

that her game is good in essence;

if she plays [gioca, possible technical term for becoming hombre] and loses, she usually shouts, I am foolish

to believe anyone anymore; he says, patience,

you will be better served another time;

she replies with a bit of fervor,

I thank you, this is a good comfort

That [?] I said it [the trump suit] was too short [referring back to stanza 5?].

10

If it happens that one has in one’s hand the three majors [note 11]

With more trumps, or Kings, she plays it alone;

to observe her plans, or errors,

the others play without saying a word

if badly teaches her the Cavalier outside,

slowly he retreats from the table.

They all piantano [?]; the Lady then shouts

Indignantly, after they had thrashed her.

_____________

Note 11, to Stanza 10. Spadiglia, maniglia, and basto.

11

But if by chance she wins the pot,

the Cavalier ascribes it to his knowledge;

therefore he puffs up, and with a cloying act

he wants to be considered a virtuoso [very expert]

but the Lady, who knows what happened,

tells him in haughty words, he should

not boast anymore, for it was an odd chance

to achieve the goal with such a game in hand.

12

There is one who, having a good game [i.e. hand]

doesn't have the courage any longer to play it alone,

therefore, Grando [?] says, I'm giving you a gift;

and they all have the desire to help her;

If it happens that she loses it; the other exclaims, I

who denied them, they make me faint,

she scolds her beloved, they make us, you know, gifts,

Ladies who give bestial pain.

13

All the Ladies, whenever they can,

have the desire to take the plate,

they reveal the corners of the aces, and turn red

in the face if someone tira [literally “pulls”: wins] and doesn't call them [chiama, technical term for choosing a partner?];

such a one complains as much as she can

and with a sour face at the end exclaims

to aspirarvi [aspire to it?] I was the beautiful fool,

a bargain that is good does not concern me.

14

To have beyond the plate also poglia [technical term, batches of tokens won on different occasions, in addition to the usual plate – 90, 60, 30 are mentioned in the printed pages]

there is such a one who demands it in full;

To fulfill such a just desire the Cavalier uses

every art and method, but if his thought fails,

with sorrow to his beloved he says straight away

that evil fate takes pleasure in best

making us remain in the lurch.

15

If one has the hand, and has a mediocre game,

and wants to tirar [literally “pull,” technical term for winning], every now and then the other

who is below [plays after her] tells them alla de mas [higher bid], so

that she makes a face of fire, and then shouts, throws out the words,

now that I had it certain, to be forced to give up

the place [technical term for being overbidden?]; then one who pretends to be learned says

Lady, you should not be disgusting,

you too will have a similar taste.

16

With such speeches the Ladies and Knights

Pass the evening playing ombre;

a great fair of plaster Pigeons clutters

the perimeter of the table; there is

shouting over a game for a whole hour,

either when they put in [si mette dentro], or when they take out [si sgombra],

nor are other whispers heard among the ladies but

tirar, riporlo, or Codiglio.

5. Comments and conclusion

Not everything is clear in these octaves; there are, as often happens, unusual terms that are justified as poetic license, but we encounter others that are typical jargon of the specific game or of players in general. To understand the text word for word I would have to insert an explanatory note for each line, or almost, but I am not competent enough to do this exhaustively. However, even if we ignore some details, the situation appears very clear to our eyes, as well as lively.

Obviously, playing two against three lends itself to livelier matches than usual, with greater possibilities of complaining about the play of one’s partners, up to the possible appearance of heated arguments. The poem in question even reflects its typical environment, and we know that we cannot place all the blame on the fair sex, as these octaves would like to suggest.

Despite the fact that the passion for this game on the part of girls and ladies of the time was also testified by other sources, it is probable that there were not many women with gaming experience comparable to that of men, especially if, as would seem certain, we are still dealing with the seventeenth century, when the "casinos, redoubts, and places where people gamble" were not yet numerous.

Probably also a lower propensity for gaming disputes is responsible for the greater favor later found by the variants for four players divided into two fixed pairs, so that in Florence they also moved from ombre to tressette and then to whist.

Florence, 04.17.2024

No comments:

Post a Comment